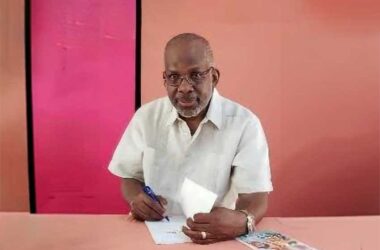

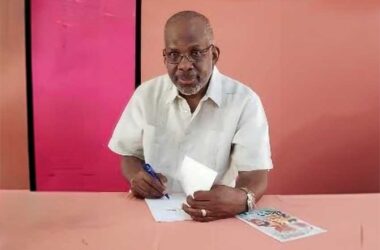

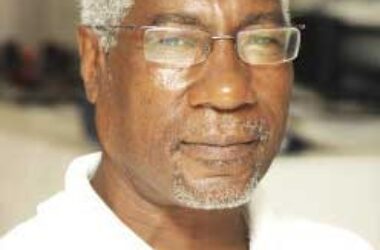

THE day Grenadian journalist Leslie Pierre died, I bowed my head to the departed veteran. He’d lived long, all of 86 years, more than half spent writing, talking and agitating as a journalist and advocate for political change – what is today called ‘Regime Change’.

Leslie and I were on opposite sides. I worked in Grenada during the Revolution — while he was in detention — both at the state newspaper and radio station, the ‘Free West Indian’ and ‘Radio Free Grenada’ (RFG).

We never met after I arrived in May 1980 or before I left at the beginning of 1982. But Leslie and I did meet in later years — all the way in the UK, where we attended a journalism seminar sponsored by the Thomson Foundation. By then — in the mid-90s – I had moved to Guyana to assume simultaneous roles as Chairman of the Board of the state-owned Guyana Television Corporation (GTV), Director at the Guyana Broadcasting Corporation (GBC Radio) and Editor of the Mirror (the ruling PPP’s newspaper).

Though I represented Guyana at the Thomson Foundation seminar, Leslie and I exchanged ideas continuously on the legacy of the Grenada Revolution, both in our formal presentations and between us. Others simply looked and listened on (some in amazement) at how we two naturally formidable foes actually peacefully coexisted day by day. We’d differ diametrically on the floor, yet sit together or astride one an other at mealtimes, or on the bus to wherever, or at the various social functions we attended in London and Cardiff (Wales).

Our exchanges were no doubt barbed, but Leslie and I always respected each other’s opinion. We agreed to disagree and actually differed on everything — except that revolutions are not run on the basis of Western interpretations of democracy and governance. He and I knew well that difference, each of us having lived it together in Grenada, at the same time — him detained and me free like a songbird.

Leslie was detained, along with over twenty others, accused of ‘acting against the interests of the revolution- — a term pregnant with the widest possible range of revolutionary interpretations and definitions. Each and all (of those detained during the revolution, for whatever reasons) always claimed to be fully and totally innocent of all the charges. Their detention was purely political and outside the realm of the inherited non-revolutionary judicial system. Leslie knew that well and did bide his time in detention, preparing for the day he’d be freed.

Leslie probably never knew his freedom would come that soon, or through US military intervention, but when it came he naturally welcomed it. The ‘Free West Indian’ was shut down and he started the ‘Grenadian Voice’, which immediately took centre stage as the leading newspaper for Grenada, Carriacou and Petite Martinique.

Our respective interventions at the Thomson seminar clearly offered our British hosts and fellow regional colleagues our stark different interpretations of what went on or down in Grenada between 1979 and 1983.

After a week in the same place, Leslie and I built in the UK a mutually respectable friendship that was extremely rare at the time between Caribbean journalists over the Grenada Revolution. Each of the few times I visited Grenada since, I visited or contacted him and we measured-up re the latest developments in post-revolution Grenada and the region.

One of the things little known or written about Leslie was that he was not an unrepentant supporter of capitalism or imperialism. Facing facts was never difficult for him, which is why he never openly expressed hate against those who had detained him. Out of incarceration, he immediately returned to his longtime pastime as an advocate of a ‘Free Press’. But while he thanked the Americans for releasing him from prison, he didn’t share the view of many jailed with him that Grenada his country should have been converted to an outright American outpost or satellite Caribbean state. He always told me his vision for his “tri-island state” was for it to be “a thriving Caribbean democracy, Western-style, but run by us Grenadians…”

Leslie was a versatile bard. He could find as much to quote from the original founder of ‘The West Indian’ T.A. Marryshow, as I could, each with our own interpretation of our selected quotes. But at all times we’d end-up laughing loudly over our agreements to disagree, rather than part with poked mouths or pleated foreheads.

The day I heard Leslie died, I spent some time looking back at how the differing interpretations of ‘Press Freedom’ played-out during and after the revolution. My roles in the Grenada media – and all my other revolutionary duties of various forms – all involved promoting and defending the revolution at home and abroad, relentless and without compromise. Youthful enthusiasm and commitment to the cause combined to propel me along. I learned on the job while sharing accumulated knowledge. We didn’t have computers back then, but the combined experiences of a large group of seasoned Caribbean journalists did help develop in Grenada a sound multi-media platform for promotion and dissemination of revolutionary information and propaganda.

The likes of Leslie Pierre and Alister Hughes (as well as Saint Lucian-born Grenada-based Leslie Seon) played their respective roles in championing their brand of press freedom before, during and after the revolution. But in the case of Leslie and Alister (who remained in Grenada during the revolution), unlike today, never once were their ideological differences and expressions of dissent ever considered by the revolutionary state to be not worthy of their lives.

The day after I mourned Leslie’s loss, the Paris Massacre took place leaving at least ten French media workers dead at ‘Charlie Hebdo’, the controversial satirical magazine. I know of no distinguished or radical Caribbean journalist who ever expressed fear of death by assassination, as in the case of the French magazine whose cartoons were so provocative as to cause the publishers to seek and receive permanent police protection from responsive attacks by those felt offended from as far back as 2006.

I know of no Caribbean journalist ready to so boldly confront religion or politics as to be accused of inviting bodily harm. There’s a limit to which we’ll go to stay alive, as much out of fear of death as out of being real. I don’t know any who’ll willingly put ourselves in harm’s way just for the story; and even though we all want to go to Heaven, none of us really wants to die. That’s why the stories of champions of ‘Press Freedom’ in the Caribbean, whatever their ideological bent, are always about them living their lives out to the fullest — until it is robbed, not by bombs or bullets, not by rotting into eternity in jail, but by failing health after a usually long life.

The Leslie I know would have wanted to live on and on. But he too, like us all, knew that none of us knows when our time will come for that last ride into the infinity of The Great Beyond. Leslie is gone, but his name — and his works – will always remain with us forever, ad infinitum.