AT an upscale hotel in the Chilean capital Santiago, I came across a few Blacks. All were Chilean – and all were waiters, cooks or housemaids. I’d seen the same before in neighbouring Argentina and Colombia, so I wanted to talk about Blacks in South America with the young guy who silently poured my coffee with a wide smile every morning. But that was out of the question, as our tongues didn’t mesh.

I wished there was a place I could go to get the history of how Blacks originally came to Chile. I didn’t just want to go to a Santiago library. Instead, I wanted a place to see that history – like a museum. But no matter who I asked, I was told there was “nowhere”.

Among my travel reading material on this my second visit to Chile was the October 2016 edition of National Geographic Magazine. As I flipped through the table of contents, my eyes caught an article entitled “I, Too, Am America!” by Michele Norris. It was about the powerful symbolism of the Smithsonian Institute’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, which had opened just weeks earlier, in September.

Anyone wanting to know ‘what it means to be American’ goes to the Smithsonian’s museums. But in this case, according to Lonnie Bunch, the Founding Director, the distinct mandate of the newest museum is “to reframe American history through an African-American lens.” She saw it as “a clarion call to remember.”

The new US $540 million museum is quite impressive. It stands at the gateway to the line of Smithsonian buildings on either side of the National Mall in Washington, steps from the White House and across the street from the Washington Monument. It is a work of African art designed by David Adjaye, a British architect born in Tanzania to Ghanaian parents.

Unlike Chile, Colombia, Argentina or Mexico, the USA now has a place where anyone (from anywhere) can easily go to find out what it is to be ‘African American’ or an ‘American Black’ today. But it didn’t just happen. Nor was the edifice a parting gift from America’s first genuine African-American President.

As I learned from the National Geographic article, the brand new building was in fact 100 years in the making. The first recorded call for (something like) it came in 1915 from The Committee of Coloured Citizens, formed to assist Black veterans visiting Washington to celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Civil War. The committee also called for “a beautiful building suitable to depict the Negro’s contribution to America.”

Several slow token steps were taken thereafter.

In 1929, President Hoover appointed Black leaders to plan a “National Memorial Building”, but they were never funded. The same happened for decades later, with Washington paying token lip service, but refusing to commit federal funds to the project.

In 1988, Congressman and Civil Rights leader John Lewis (a Democrat) introduced a bill for a museum –and re-introduced it every year thereafter. But in 1994 the veteran racist Senator Jesse Helms killed it, saying: “Every other minority will give thought to asking the taxpayers to pony-up for a special museum for them.” However, in 2001, Black Congressman J.C. Watts and White Senator Sam Brownback (both Republicans) joined Lewis to help push the legislation.

Truth be told, this is not the first museum dedicated to Black History in America. In 1967, Smithsonian opened a Museum of Black History and Culture in Anacostia, an Afro-American community in Washington. In 1981, Congress also authorized the National Afro-American Museum in Ohio — but it runs without Federal funds.

However, the first call for “a museum on the Mall” came in 1996 from Tom Mack, a Black Washington tour bus operator, who launched a campaign for it. Then in 1990, to draft a plan, Smithsonian established the National African-American Museum Project.

In 2003, President George W. Bush signed legislation to establish the museum; in 2006 a site was selected near the Washington Monument; in 2008, the museum started collecting “African-American treasures” across the US; and at the groundbreaking ceremony for the museum’s construction in 2012,

President Barack Obama said “it should stand as proof that the most important things in life rarely come quickly.” Then in September 2016, the museum moved into the new sparkling edifice.

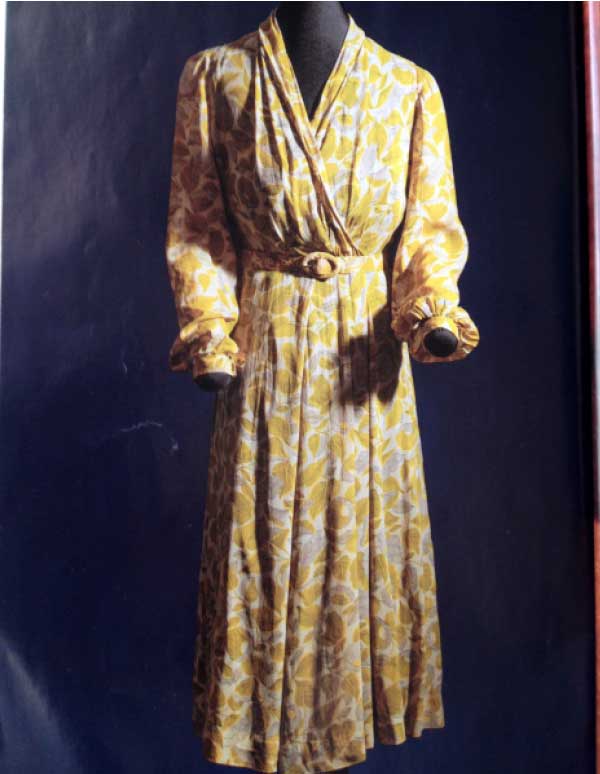

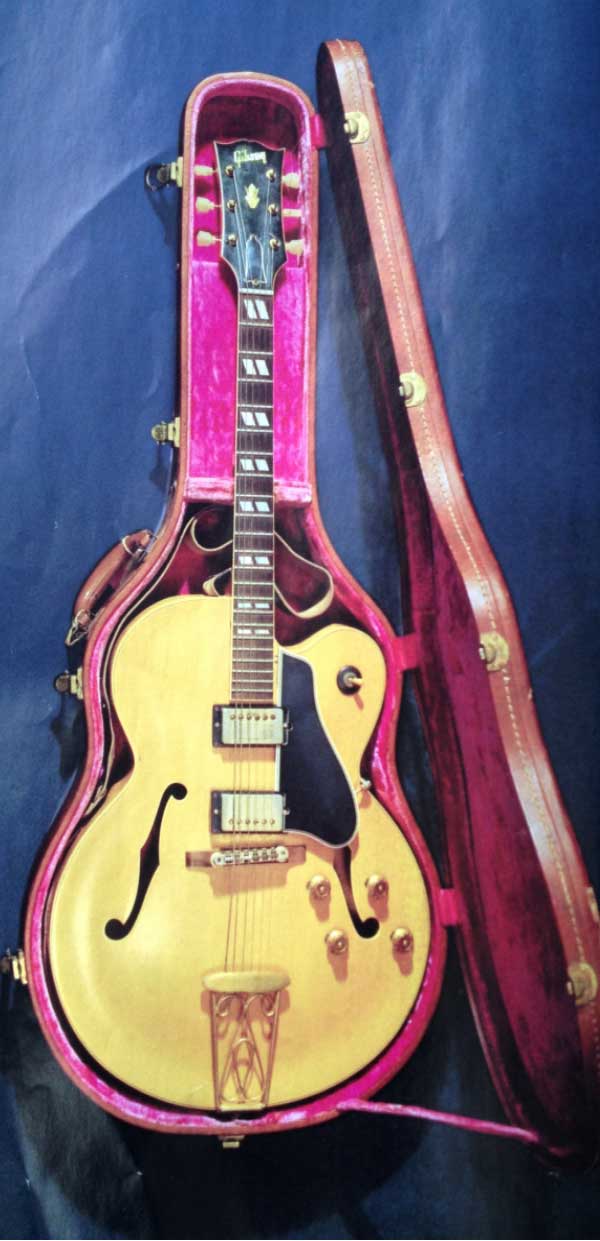

So, what to find there? Everything that can tell a piece of the African American’s history: ‘Freedom Papers’ of freed slaves (who had to produce them on demand); iron shackles for slave children; the hymnal carried by abolitionist Harriet Tubman; the bible owned by Nat Turner (a Black preacher who led several slave rebellions in south Virginia and always had the Holy Book on hand, even in battle); a photo of the all-Black 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment in 1863; war medals from France honouring members of the all-Black 369th Infantry (also called “The Harlem Hell-fighters”) during World War I; the dress sewn by Rosa Parks, the civil rights activist and seamstress who refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus to a white man, leading to the 1955 Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott; a Jim Crow-era segregated railroad car; the Cadillac driven by rock-and-roll legend Chuck Berry; the inkwell used by James Baldwin; Carl Lewis’ Olympic Medals – and more.

This is indeed the place were Black Americans can go and learn their history and contribution to America – and why, like Baldwin yesteryear, they can confidently say today: “I too, am American!” But where else in this part of the world can Blacks with African roots go and do the same?

What African Americans finally have now is also being sought by 15 governments of majority Afro Caribbean states where African slaves were also deposited during Europe’s criminal but lucrative slave trade.

CARICOM states are collectively seeking ‘Reparations for Slavery and Native Genocide’ from Britain, France and other European Union (EU) member-states and promising to establish a similar Museum of African-Caribbean History — if the Europeans agree to atone.

The first recorded call for Reparations for victims of the Slave Trade was made in London in 1897 to Queen Victoria’s Royal Commission on Reparations by Saint Lucian John Quinlan, on behalf of the Pan African Congress (PAC). He also spoke in the name of the slaves ‘freed’ by Emancipation, but still locked in chains of poverty half-a-century after ‘abolition’. Marcus Garvey continued the ‘Reparations or Repatriation’ call in the USA and the Caribbean decades later, which was picked-up by the likes of the US-based Nation of Islam and the Rastafari movement in Jamaica.

CARICOM’s first call for Reparations – the first ever by governments — was made in 2013, when the governments adopted a 10-point ‘Plan of Action for Reparatory Justice’. A relevant section states: “European nations have invested in community institutions such as museums and research centres, which serve to reinforce within the consciousness of their citizens an understanding of their role in history as rulers and change agents. With no such institutions in the Caribbean, descendants have no relevant institutional systems through which their experience can be scientifically told. This crisis must be remedied within the Caribbean Reparatory Justice Programme.”

CARICOM governments have not received any positive response from Britain to their call for dialogue on reparations for slavery and native genocide in the Caribbean. Then Prime Minister David Cameron rejected outright any talks on reparations — and there’s no word yet from his successor Theresa May, who in her first week in office announced she was allocating 30 million pound (sterling) “to end modern slavery in Britain”.

But while no one expects it to take another 100 years to see it really happen, still no one can say how early to expect it to.

In the meantime, the Afro Caribbean treasures that will eventually fill such a museum to the region’s dominant history and culture continue to be treasured by persons and families, in homes and communities, in the islands and mainland territories that comprise The Caribbean Community.

![Simón Bolívar - Liberator of the Americas [Photo credit: Venezuelan Embassy]](https://thevoiceslu.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Simon-Bolivar-feat-2-380x250.jpg)