The Passion, the Pain, and the Power.

(This article by Andrew Antoine is a brief history of the Saint Lucia Labour Party (SLP) to coincide with its 65th Anniversary Conference this weekend.)

=======================================

PART ONE

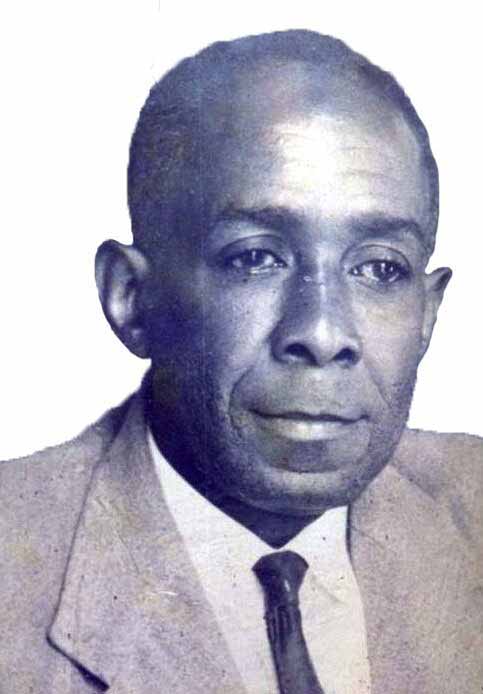

The SLP political leader, George Charles, sat with bowed, thoughtful head in his humble living room. It was 1966, and, two years earlier, on 25th June, 1964, his party had suffered a humiliating defeat at the polls. Since that shock defeat, members of his Executive Committee had begun questioning the wisdom of his continuing leadership. The Committee had become focussed on whether the Labour Party required a new image, to recover from the eight-two beating suffered at the hands of the UWP at the last general elections.

How did it come to this? What events had conspired to derail the dominance of his working class Party and plunge it into opposition? What had driven the masses to abandon the champions of their interests for a Party that had in its ranks members of another Party who represented the interests of the plantation class? Hadn’t they tasted the slave-like conditions of work, the terrible wages, their small children working in the fields alongside them so they could reach their daily quota, and their inability to alter the rules, regulations or laws governing them under the oppressive plutocracy? So, what had caused this massive shift? George Charles knew the answers, of course! But, he had become a haunted man—haunted by agonizing images of brutal struggle, spilt blood, victory, and betrayal. And, as he had done so many times after 25th June, 1964, he allowed his mind to drift back to the early days of the struggle.

More than eighty years after the abolition of slavery, working conditions for surviving freed men and women, and their progeny, had not changed much. Plantation life, characterized by a twelve to fourteen hour work day from Monday to Sunday, was backbreaking. Small children, eight years or older, worked alongside their parents so the daily work quota could be achieved. Wages were a mere pittance, with men receiving a little more than women. Workplace accidents, some of them fatal, were common. There was very little or no compensation to injured workers or the family of a worker killed as a result of an accident on the job. And, on top of all of that, social discrimination against blacks was just as bad as it was during the pre-emancipation period and in some instances, even worse. Those were the conditions that ignited a powder keg of seething discontent in 1937 not only in Saint Lucia, but almost every other island in the Caribbean as well.

Strikes, riots, arson! The acidic rage that had been simmering just below the frail surface of a restive calm erupted to the surface, and exposed the ugly underbelly of a callous colonial system. Alarmed at the Caribbean-wide rebellion, the British government appointed a Commission of Enquiry led by Lord Moyne (Walter Edward Guinness) to investigate the causes. And the trade union movement was born!

It began as a tiny spark. Enshrined in the Moyne Commission’s report was a recommendation that workers in the region establish trade unions to protect themselves from the ruthless exploitation of their employers. Although trade unionism was virtually unheard of in Saint Lucia, the tiny spark lit in the breasts of workers desperate for better working conditions and wages, was gradually fanned into a raging inferno by emergent leaders. Opposition to this newly minted idea was fierce. From mockery to attempts at preventing public meetings to the use of force, everything was used to destroy trade unionism in Saint Lucia even before it began. But, workers and their leaders were equally defiant. Braving the onslaught of the colonial minority and their agents, they resisted all attempts to stop them. Their efforts culminated in the introduction of trade union legislation, and the registration of the first trade union in Saint Lucia in 1940—the Saint Lucia Workers’ Cooperative Union. (The Saint Lucia Workers’ Cooperative Union became the Saint Lucia Workers’ Union years later.) This was followed by the formation of the Seamen and Waterfront Workers’ Union in 1944, and the St. Lucia Civil Service Association in 1951.

Forged from the industrial relations heat of the trade union movement, the ideas and cementing of ideals arising from those ideas helped to shape George Charles’s thinking and propel him into the ranks of leadership. He never balked or wavered. Armed with the conviction and certainty of moral right and outrage, and the provisions of the trade union legislation, he and the other executive members of the Saint Lucia Workers’ Union stormed the entrenched anti-worker attitudes and practices of the minority élite. Simultaneously, they stoked the awakening consciousness of workers— who, it appeared, had begun to appreciate the power of numbers and united struggle— through education, information dissemination, and the sheer strength of their own convictions. Their stage became the Castries Market Steps, and the very large crowds which gathered to listen to and take instructions from them, harkened to the unionists repeated calls to join the union. A new revolution had begun!

Trade union registration was one thing, recognition from employers quite another! With workers in full battle cry, however, and the membership of the Saint Lucia Workers’ Union showing approximately five thousand financial members by early 1946, the first ever wage agreement was signed between the union and the sugar manufacturers. The agreement included increased wages for both men and women, an eight hour day, and overtime pay. Castries bakery owners, who initially refused to heed the union’s request for negotiations on behalf of their members, faced the first official strike in Saint Lucia, which lasted for five days. During that period, they were forced to negotiate because of their contractual obligation to provide bread to the Eastern Caribbean Regiment in Saint Lucia.

One of the last bastions of resistance to union demands was the Castries Town Board. In 1947, it became obvious to the executive members of the union that they needed to place their members on the Board so they could exact improved wages and working conditions for the workers. At the end of that year, elections for the eight positions on the Board were held. The union fielded four candidates from their executive to break the stranglehold members of the middle and upper classes had on that institution. Although only one of their members was elected to the Board because voting was limited to those at or above a certain income, they vowed that “one by one” would eventually fill the basket. The Castries fire of June, 1948, changed things faster than the unionists ever thought possible. After the fire, there wasn’t even a pretense of class distinction, as so many of the Castries residents had lost all their possessions in the fire. The ensuing perception was they were, now, all in a bitter struggle together and had to exist as “one family” helping each other. As a result, the December, 1948, elections to the Town Board ushered in four trade unionists. And, in the new spirit of unity, understanding, and cooperation, a new wage structure was established for the Town Board workers.They were now entitled to vacation with pay, gratuity, and pension allowances to those who reached the age of fifty-five and had served for at least ten consecutive years.

Something once thought immovable and permanent had begun to change. Union leaders and the workers they represented began to see a glimmer of a new life they never thought possible. Thoughts they had never dared to entertain began crowding their minds. Soon, they didn’t just begin to think and dream of a new life, they also began giving voice to their thoughts and dreams, and the vehicle through which to solidify them. Determinedly, they cranked up the machinery of their revolution.

Universal Adult Suffrage—the right of every citizen at or above a certain age to vote—was the new goal! Crown Colony Government had become a very sore and vexatious point for union leaders and workers who had grown tired of being governed by an expatriate, English governor taking instructions from Britain. They wanted a major say not only in how the country was being run, but also in the mechanisms devised to run it. They wanted a fully elected Legislative Assembly and an Executive Council with a majority of elected members. In resolution after resolution to the British Government, union leaders demanded this as a right, notwithstanding the fierce opposition from expatriates and their allies, who stubbornly wanted to maintain the status quo and thus keep the great majority of the population “in their place”. They were not alone. Unions and other organizations in almost every other Caribbean island joined in the struggle for Universal Adult Suffrage, until, in 1950, the British government announced its decision to grant most of its colonial territories in the Eastern Caribbean exactly that.

Although the Saint Lucia Workers’ Union leaders had started the decline of colonial rule, Crown Colony Government was still very much in evidence. It was time to shift gears yet again. It was time to intensify the struggle for self-determination and nationhood. It was time to introduce a political arm into the structure of the union so that all citizens, workers and non-workers alike, could truly enjoy all the benefits of a free society. This was the idea which gave birth to the Saint Lucia Labour Party (SLP) in October, 1950.

![Simón Bolívar - Liberator of the Americas [Photo credit: Venezuelan Embassy]](https://thevoiceslu.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Simon-Bolivar-feat-2-380x250.jpg)