BACKGROUND

About a month ago, I was invited to interview Miss Jessie Stephens while she was on island for a conference of the Saint Lucia Association of London (1963). Her name immediately rang a bell. From the snippets of information I received, I was able to trace its origins in my consciousness to Mr. Nicholas Taylor—former High Commissioner in the UK for the West Indies Associated States between 1962 and 1973–who was a very dear friend of my father.

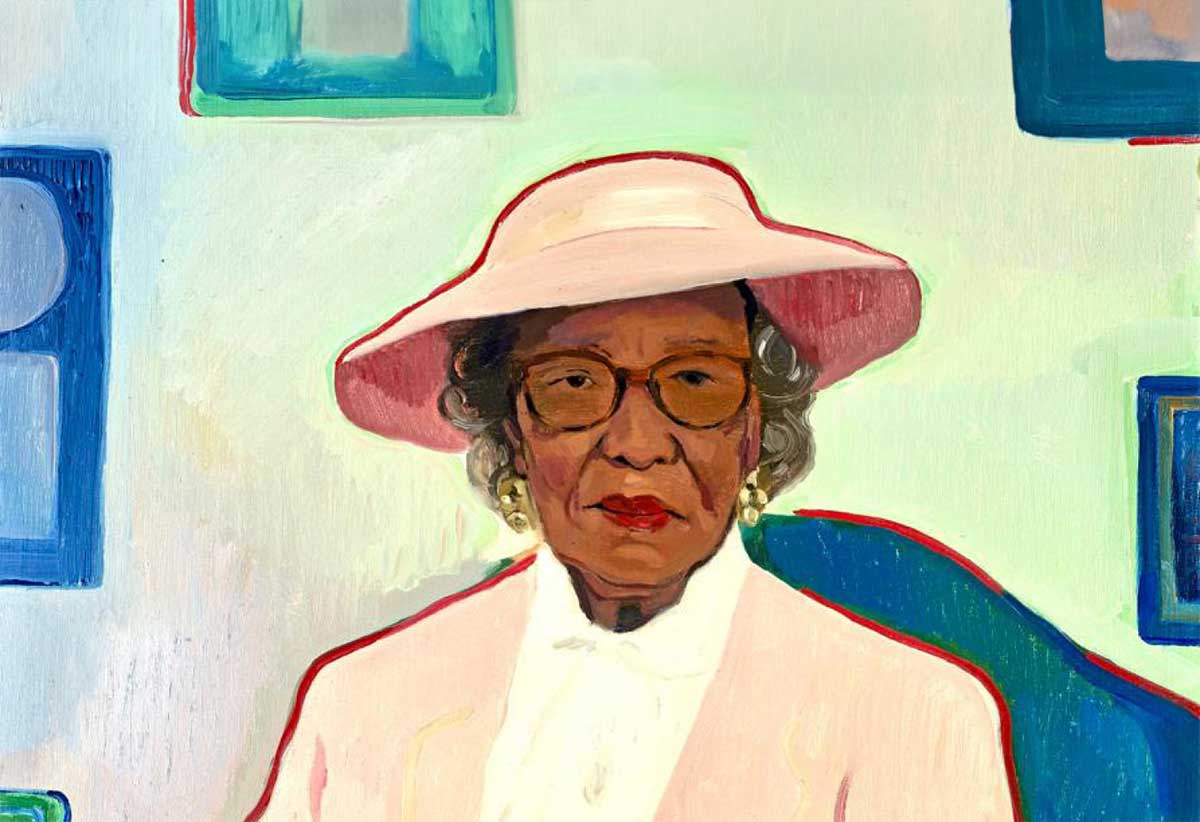

Well before I walked into the lobby of the Coco Palm Hotel, I’d already formed an early opinion of Miss Stephens as a “femme formidable” (formidable woman). Our first few minutes together would confirm this. I was introduced to a diminutive lady with silvery-grey hair protruding almost reluctantly from beneath a black, narrow-brimmed hat. She had a quiet, steely demeanor that suggested character and resolve. She flashed an eager smile as we shook hands. She too was familiar with my family, especially my father and deceased brother Winston. I mused that if Winston was still alive, he would have thoroughly enjoyed interviewing her. Only weeks earlier, she’d celebrated her 96th birthday, but as we prepared to move from the lobby to the interview room, she rose from her low chair with more ease than someone half her age. She walked unassisted and with a steady gait to the room.

War Memories

She was 11-years old at the time, but Miss Stephens easily recalled Saint Lucia’s experience during the Second World War especially the attacks in the early hours of March 10, 1942, by a German submarine on two supply vessels–the “Umtata” and the “Lady Nelson” — that were docked in the Castries Harbour. Both vessels sank but were later salvaged, repaired, and returned to service. The incident claimed 35 lives, including crew members and passengers on both ships and dock workers.

Journey to the Unknown

Miss Stephens spoke fondly of her first trip to the UK aboard the “HMS Bianca C.” The name brought back vivid memories of my first visit to Castries Harbour with my family to bid farewell to my brother Denys who was headed for the UK in 1962. About a year later, we were back, to see off a second brother, Peter who left aboard the “HMS Ascania.” These were the only passenger vessels that serviced the Caribbean to UK route. Miss Stephens was then 28-years old, and like most, if not all of her fellow passengers on the 16-day journey, she was hopeful of having a better life in the UK. Her brother, who had already migrated to the UK, had convinced her of this and had assured her it would be possible to work by day and study by night.

Settling In

Things started out a bit shakily, as upon her arrival in the UK, her brother was not at the seaport to meet her. Unknown to her, he was in hospital recovering from ear surgery. There was no way she could have been told about this while en route to the UK. She and fellow Saint Lucian migrant, Geraldine Girard were assisted by an officer of the Home Office who placed them in accommodation at a hostel in Aberdeen Park in Highbury.

First of Firsts

The excellent stenography and shorthand writing skills she acquired at home would serve Miss Stephens in good stead when she applied for and was appointed as Clerk/Stenographer at Companies House—the UK version of Saint Lucia’s Registrar of Companies. It was an historic appointment as she was the first black woman to work at “The House.” Asked about that experience she replied: “Nobody bothered me. When I was spoken to, I answered. Whenever my assistance was needed, I gave it.”

Latchkey Kids

Miss Stephens did not experience any overt racism during the two years that she spent at Companies House, before she was transferred to another part of the Civil Service. However, she insisted that racism was an issue in the wider UK society at the time and was part of a toxic mix along with social exclusion, police brutality and poverty that impacted the lives of poor and marginalised youth in the London Borough of Haringey. Left unsupervised while their parents were at work, these “latchkey kids” as they were called were at risk of being perpetrators or victims of crime and anti-social behaviour. “These were hungry 10 and 11-year olds who broke into homes in search of food; but they were locked up,” she explained.

Race Relations

Consequently, when it was announced that a Haringey Police Liaison Group would be established to improve race relations between the police and the community, Miss Stephens—who was already a member of the Haringey Race Equality Council —immediately volunteered to serve. After contacting the Detective in charge of the initiative she turned up the next day at the Police Station, but the desk officer (Sargeant) at the time of her visit was unwelcoming and bluntly said her services were not needed. After reestablishing contact with the Detective, she was made a member of the group which, over several years worked at understanding and influencing community safety, policing decisions and policies that affect them; and to hold the Metropolitan Police to account for the services at local level. Still, despite the best efforts of the Group, minorities in Haringey continue to face social deprivation and economic hardship, with high levels of poverty, unemployment, and homelessness. These and other negatives facing minorities across the UK left Miss Stephens in no doubt that race relations in the UK had not progressed and in fact had worsened.

Diaspora Devotion

It would be in the service of her country and its people that Miss Stephens would make her most indelible mark. She became the “alpha and omega” of the St. Lucia Association of London 1963, working under the leadership of deceased Primrose Bledman and Seton Campbell. Over nearly six decades, until her retirement as General Secretary in 2019, she has etched her name in the minds and hearts of virtually every Saint Lucian migrant who has interacted with her. In that role, she directed and/or supported countless fund-raising efforts —dances, raffles, boat rides—for various causes at home, that included educational projects, youth activities, support of the poor and destitute, health projects, fundraising in times of disaster e.g., hurricane, personal disasters suffered by local inhabitants (fire or medical needs), and support for charitable infrastructure programmes. In June 2023, the Association presented cheques totaling £2500 to CARE, the Crisis Centre and to a student at the SALCC.

Novelist, poet, actor, and playwright, MacDonald Dixon, who interacted with Miss Stephens while studying in the UK and later as General Manager of the National Commercial Bank (NCB), related to me that upon assuming duties, he found that the NCB —not unlike other indigenous banks in the region—had a severe foreign exchange problem. Propelled by a brain wave he traveled to the UK on the wings of hope that if he could get Saint Lucian migrants in the UK to do business with the NCB, that would ease his foreign exchange headaches. He readily acknowledged that it was primarily through the invaluable efforts of Miss Stephens that he was able to raise £5 million in business for the bank.

Miss Stephens also served as a member of the African-Caribbean Leadership Co Ltd., which was formed in 1975 by members of the “Windrush Generation”—a term used to describe the migrants who arrived in the UK between June 1948 and 1971. Most of the 1027 migrants who arrived in Tilbury aboard the HMT Empire Windrush on 22 June 1948 were from the Caribbean and many had served with pride and honour in the Second World War. In this role, she helped to service the needs of the African Caribbean community in Haringey and its surrounding areas.

Appreciation and Praise

Miss Stephens’ invaluable and indefatigable efforts have been lauded by every Head of State and Government of Saint Lucia as well as every High Commissioner posted in the UK since 1963. In 1986, she was honoured by Queen Elizabeth II with an MBE for her services to her community and was further awarded a St. Lucia Les Piton Medal (SLPM) for her continued dedication and services throughout the diaspora. Her most recent honour came in —2023 when her portrait was one of 10 unveiled at a reception hosted by King Charles at Buckingham Palace showcasing pioneers of the Windrush Generation.

Sadness Amidst the Acclaim

While she’s proud of the many honours she has received, Miss Stephens shared her distress over the humiliation suffered by some undocumented, surviving members of the Windrush Generation and their families. Two days after the HMS Windrush brought its first batch of migrants to the UK, a group of 11 Labour MPs had written to then Prime Minister Clement Attlee calling for a halt to the “influx of coloured people.” Seventy years later, the Theresa May administration would heed that call. Surviving migrants and their children who had travelled to the UK on their parents’ passports were wrongly detained. Some were threatened with deportation while about 83 others were returned to the Caribbean, many to Jamaica. Miss Stephens does not recall any Saint Lucians being deported; but she grieves for those who were, and who had their dignity and identity stripped from them. “We tried to encourage them to put their affairs in order, but for various reasons, many did not act until it was too late,” she lamented.

The Future

Miss Stephens offers a matter-of-fact description of her future, which unsurprisingly, is defined by her age. She chuckled at my observation that she didn’t look her age. “I don’t feel it” she confirmed. And when I asked her how she planned to use the many years she had left, she laughed. She replied that her main goal was to apply what time and energy she had left towards renovating “the Centre” which had served as the “Mecca” of sorts for Saint Lucians residing in the UK. The building had deteriorated during the Covid years, and she was keen to raise the funds to return it to its primary use as the centre of recreation and social relations among the Saint Lucian diaspora in the UK.

It was with much reluctance that I ended my chat with Miss Stephens as there was a lot more that I could have discussed with her. We agreed to pick up the discussion soon, hopefully in the UK. As I returned to my car, I offered a silent prayer that this formidable lady would have many more years among the people she has loved so deeply and served so diligently served over six impactful decades.