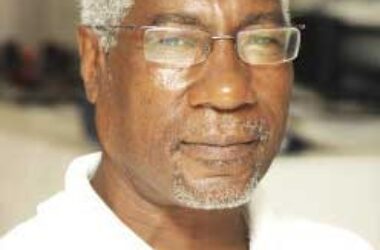

(The writer is Antigua and Barbuda’s Ambassador to the United States and the Organization of American States. He is also a Senior Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies at the University of London and Massey College in the University of Toronto. The views expressed are entirely his own. Responses and previous commentaries: www.sirronaldsanders.com)

THE relationship between the United States of America (USA) and the 14-member independent member states of CARICOM as well as the Dominican Republic has entered a new phase of cooperation after seven years of neglect between 2015 and 2022.

Renewed US interest in the Caribbean region as a whole, as distinct from a preoccupation with Cuba and Haiti, began at the Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles, hosted by President Joe Biden in June 2022. At that meeting, many Caribbean leaders insisted on a collective meeting with the US President to place serious issues of concern before him.

Prior to the Los Angeles meeting, no engagement between Caribbean leaders, collectively, and a US President had taken place since Barack Obama held a fleeting encounter with them in Jamaica in 2015.

Donald Trump had no engagement of any kind with Caribbean leaders, collectively. In March 2019, Trump held what many political commentators regarded as a divisive meeting with leaders of five Caribbean countries at his personal estate, Mar-a-Lago, in Florida. That perfunctory meeting with the Heads of Government of The Bahamas, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Jamaica and Saint Lucia was not in the least bit substantial. Of the Heads of Government who met Trump only the Jamaican Head of Government is still in office.

Trump was encouraged to hold it by his political advisers as a gesture of appreciation to the five leaders who joined him in recognizing Juan Guaidó as the President of Venezuela – a decision which continues to have adverse consequences in the Hemisphere. The promises he made to these five leaders of assistance on various matters never materialized.

Eighteen months of President Biden’s administration elapsed before he – and his policy-making team – widened their Caribbean attention beyond Cuba and Haiti. On Cuba, the Biden team had largely continued the hardline policies inherited from Trump, and, regarding Haiti, the principal concern was restricting the constant flow of refugees, fleeing to the US to escape what was, even then, a humanitarian crisis.

The game changer was the meeting in Los Angeles in the margins of the 2022 Summit of the Americas where Caribbean leaders were persuasive in setting forth the crucial interests shared by the US and the Caribbean. There were, perhaps, two underlining but unspoken issues that helped to re-ignite USA interest in the Caribbean. The first was the growing economic, political and diplomatic presence of China in the Caribbean and Latin America, and the other was a new assertiveness by the leftist groups in Latin America who were being elected to government, challenging the traditional US sway over the area.

What the US saw as great value in the Caribbean was that, with the exception of Haiti, the 14 CARICOM countries and the Dominican Republic were relatively stable democracies, the majority of which were motivated by their development needs and not by ideologies. Strengthening relations with this group was certainly in the interest of the US.

Regarding China, realization had dawned on US policy makers that China was filling a vacuum that the US had left in the provision of financing for development and, as a consequence, had become a serious rival in what the US had traditionally regarded as its sphere of influence.

The wheels of a new cooperation were set in motion with three joint committees established to pursue energy security, food security, and access to financing. While no dramatic results appear to have been achieved by these three Committees, at the very least the US has re-engaged in the region. On June 8, 2023, US Vice President Kamala Harris met Caribbean leaders in The Bahamas in furtherance of enhancing the US-Caribbean relationship.

It was clear from the US State Department’s read out of the meeting and the statement issued by the CARICOM Secretariat, on behalf of the Caribbean leaders, that apart from the usefulness of the meeting to ventilate concerns, matters had not progressed in ways that could cause Caribbean leaders to describe it other than as “a useful platform for productive discussions”.

Similarly, the US State Department did not describe outcomes beyond stating that among the issues “discussed” were: cooperation to address the climate crisis and the transition to clean energy; ways to strengthen energy security and enhance resilience; and adaptive capacity to withstand the impacts of climate change and extreme weather events.

Still, the US is maintaining a dialogue. So far, it has not delivered results with the immediacy that the Caribbean might like, but this may be due to difficulties of coordination and implementation on both the Caribbean and US side that require fixing. It is in the Caribbean’s interest to establish a single, focused mechanism, much like the original 1997 Regional Negotiating Machinery, which was given the authority under Heads of Government guidance to negotiate the region’s trade and investment relationship with the European Union.

On the same day that Vice President Harris was meeting Caribbean leaders in The Bahamas, three influential members of the US House of Representatives announced the introduction of the “US-Caribbean Strategic Engagement Act of 2023”, which they describe as “a comprehensive roadmap to modernize U.S. engagement with Caribbean nations”.

The US Congress holds the strings to the purse of US monies and the authority to set priorities and instruct on the release of funds. Therefore, this initiative by Joaquin Castro (Texas), María Elvira Salazar (Florida), and Adriano Espaillat (New York) should be bolstered by Caribbean endorsement and support. It requires work and a coordinated Caribbean effort, which could well be placed in the hands of the same single, focused mechanism described earlier in this Commentary.

Responses and previous commentaries: www.sirronaldsanders.com