Straight away, I must state that this commentary is not about proving or disproving the claim by “The Mighty Sparrow”-aka Slinger Francisco-that it was Napoleon who started the French craze of kissing as a show of affection. It is not about the best-selling book, released in the 1940s entitled, “60 Million Frenchmen Can’t Be Wrong” about the cultural differences between France and the United States. Rather, it is inspired by another book of the same title, written by Julie Barlow and Jean-Benoît Nadeau, which helped to dispel what was then considered the conventional wisdom that the French were resisting globalization, when in fact, they were profiting from it.

Conventional wisdom is commonly defined as a set of ideas or assertions that are generally accepted by the public and/or by experts in a field. But as American musician and music journalist, Steve Albini, admonished us, “conventional wisdom should be doubted, until it can be verified with reason and experiment.” Indubitably, this is sound advice. We should never flinch from challenging popular beliefs that don’t make sense. To do otherwise would be tantamount to surrendering our intellectual curiosity and capacity for independent, critical thinking. Admittedly, these are uncommon attributes.

The thing is, it’s easier to ignore the conventional wisdom, than it is to challenge it through reason and/or experiment. Moreover, to conclusively challenge conventional wisdom, one must apply at least the same level of reason and experiment that helped to establish the conventional wisdom in the first place. For the average citizen, this is nigh impossible, and for small island developing states, it can be extremely difficult, as curators of the conventional wisdom often have a sufficiently strong, vested interest in its longevity, to either frustrate efforts to disprove it, or to ignore those who succeed. This is especially the case with conventional wisdom that’s imposed on countries, in ways that deny them the ability to question such wisdom, and/or even to evaluate it for themselves. Whenever developing countries come up with original, innovative ideas, the default disposition of developed countries is that until they “clear” these ideas or inventions, they have no value, and cannot be marketed or otherwise exploited. Here, we might recall the brouhaha over coconut oil, which began in the late 1990s, and which continues in some countries, despite the dubious and still unsettled science regarding the saturated fat content of coconut oil, and its link to heart disease.

The Wisdom on Subsidies

Perhaps the area in which conventional wisdom is most prevalent is international development economics. Over the last century, countries have oscillated between free market and state interventionist doctrines. Amidst these doctrinal swings, the one constant has been tension between economists and policy makers in developed countries, and between them and their counterparts in developing countries. One example of this tension is subsidies, which for many decades now, have been like “bees in the bonnets” of international finance institutions (IFIs), like the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). These institutions have been trying to discourage Caribbean countries from granting incentives to local and foreign investors, which they claim cause “artificial imbalances between supply and demand and make it difficult for market actors to recognize the true price of an output or product.”

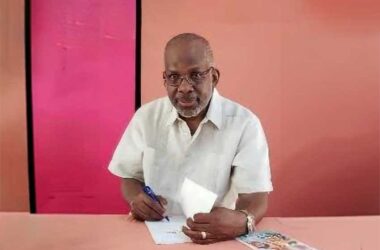

This “wisdom” was reinforced at every meeting that I attended, as Alternate Governor of the WB between 1994 and 1997. It was repeated during a bilateral meeting between Saint Lucia and the WB which was held during an annual World Bank Meeting in Washington D.C, in the fall of 1996. On that occasion, Saint Lucia’s delegation, led by then PM, Dr. Vaughan Lewis, was sharply chastised by a senior WB official for maintaining its “market distorting subsidies” to the agriculture and tourism industries. As the official spoke, I could see a gradual reddening of Dr. Lewis’ dark face. I sensed he was about to “lose his cool.” Just as I was about to ask whether he’d like me to respond, he seemed to read my mind, and gave me “the floor.” Knowing his strong views on the matter, I felt reasonably confident I could share them at the meeting, with his trademark clarity, but without his unnatural ire.

In my response, I noted that the Windward Island’s banana industry was already under assault from the US and its consorts in Latin America. I pointed to the many, varied, and costly subsidies given to the fossil fuel industry, airplane manufacturers and farmers in developed countries. Then, I pointedly asked the WB official, whether he cared that Saint Lucia’s adoption of the bank’s subsidy reform policy would likely place 12,000 Saint Lucian farmers on the breadline and unleash untold social unrest in our country. My question was a rhetorical one, as at that time, our banana farmers had already begun their quest for “salvation” from the Compton Administration whom they blamed for their perceived hardships. My question elicited no response from the WB official and the meeting moved on to other matters.

I readily admit that subsidies to our farming and tourism sectors can be better managed and made more efficient, especially to reduce wastage and abuse. We saw evidence of this inefficiency and wastage during the peak years of the banana industry, when fertilizer–which was heavily subsidized, or given free-of-charge to farmers–was misapplied and/or wasted. The negative human and environmental health impacts of this wasteful practice have not been fully evaluated. In the first half of the 1990s, the Caribbean Environmental Health Institute (CEHI) assessed pesticide levels in the urine of farmers which raised a few red flags. When I left the Institute in 1992, plans were afoot to assess pesticide levels in the blood of farmers, which would have produced more conclusive results. I don’t know how that went.

However, what irks me about the conventional wisdom of the IFIs on subsidies is their willful disregard of the subsidies culture in developed countries. Consider this. In 2019, the United States won the largest arbitration award in World Trade Organization (WTO) history in its dispute with the European Union (EU) over illegal subsidies to Airbus. This followed four previous panel and appellate reports from 2011-2018 finding that EU subsidies to Airbus broke WTO rules. The US was awarded US$7.5 billion in annual penalties, which is by far the largest award in WTO history. Eight years earlier, the WTO ruled that Boeing received at least $5.3 billion in improper aid (subsidies) from the U.S. government, including money for research and development from NASA, which gave Boeing an unfair advantage over Airbus.

Environmental Sustainability

Another area in which conventional wisdom has become well-entrenched is global environmental sustainability. In the run-up to the first UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in 1992, many representatives from the Group of 77 and China-the main negotiating bloc for developing countries within the UN-openly voiced their suspicions that the hidden purpose of the sustainable development movement being pushed by the North (developed countries) was to stifle economic development in the South (developing countries). The argument was that having despoiled the global environment in their push for development dating back to the Industrial Revolution, the North was now calling on countries in the South to practice sustainable development.

Now, please don’t get me wrong. I’m all for sustainable development. To me, it’s counterproductive for developing countries, especially SIDS with limited natural resources, and who are highly dependent on tourism, to undermine the very environmental assets that undergird their development. These sentiments came to mind as I viewed a viral video with excerpts of a BBC “HARDtalk” interview between host, Stephen Sarkur and Guyana’s President, Dr. Irfaan Ali regarding the climate harming effects of the release of over 2 billion tons of carbon from Guyana’s oil and gas sector. While it’s Sarkur’s nature to be provocative, I had great difficulty accepting this, as I observed his demeanour and listened to his tone and his line of questioning. I thought Dr. Ali acquitted himself well.

The fact is, no country with proven oil reserves has kept it in the ground, as Greenpeace and other global environmentalists have been advocating. To expect a country that for decades occupied the bottom rungs of the global socio-economic ladder, and that is burdened with a 40% poverty rate, would do what no other oil-rich country has done, is illogical in the extreme. The ideal scenario would have been for those countries who claim to be concerned about the climate harming impacts of Guyana’s O&G industry, to guarantee the country the equivalent revenue that would be lost if it kept it oil in the ground. This has not happened, and it will not happen. And if I was in the shoes of President Ali, I would reject any such assurances from developed countries, whose portfolio of unfulfilled promises to developing countries is dwarfed only by the size of Guyana’s oil reserves.

In any event, it’s highly unlikely any such compensatory instrument would have the same multiplier effect as actual O&G production in Guyana. According to Exxon Mobil, approximately 6,200 Guyanese are directly employed in the Stabroek block operations alone. Exxon claims it and its contractors have spent over US$1.5 billion with Guyanese suppliers between 2015 and 2023, and that oil production has contributed $4.5 billion to Guyana’s Natural Resource Fund (NRF), which functions like a sovereign wealth fund. The IMF, in its Annual Assessment of Guyana, described the three key purposes of the NRF as helping to: (1) delink public spending from the volatility in natural resource revenues; (2) ensure natural resource revenues do not lead to a loss in competitiveness; (3) fairly transfer natural resource wealth across generations; and (4) use natural resources wealth to finance national development priorities and any initiatives aimed at realizing an inclusive green economy.” From this we can deduce that decent safeguards are built into the management of the country’s oil revenues.

The Hazards of NET ZERO Arithmetic

In the HARDtalk interview, President Ali noted that carbon emissions from Guyana’s O&G industry would be comfortably offset by the 90.5 giga-tons of carbon sequestered in its massive Iwokrama forest. However, he neglected to mention that this contribution might not have been possible without substantial financial support from Finland and the Commonwealth of Nations, through the Commonwealth Secretariat. This brings me to the challenge I’ve always had with the 2015 Paris Agreement (PA) which replaced the Kyoto Protocol (KP) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC). Whereas the KP rightly placed the burden for climate change mitigation on major emitters of carbon and other greenhouse gases, the PA shares this burden among all signatories to the UNFCC and commits them to maintain at least, “net zero” status, meaning they must remove as much carbon as they produce, to help the world to avoid the worst impacts of climate change, by 2050. That horse has already bolted. However, crucially, SIDS with negligible carbon emissions and sizable EEZs that serve as carbon sinks received zero compensation from the key polluters. So, when President Ali proudly cites his country’s super, net-zero status, practically all SIDS can make a similar claim, yet they suffer disproportionately from climate change because they don’t have the money to invest in climate change adaptation. Hopefully, Guyana will consider the plight of its Caribbean neighbors and other SIDS when deciding on the use of its massive NRF financial reserves.

Non-Productive Lending

Another piece of conventional wisdom that is pushed at developing countries is that they should not borrow for activities that do not contribute directly to economic growth and generate foreign exchange. I fully agree that as with all loans, countries must consider all pertinent contextual factors such as national, regional, and global economic growth projections, export performance, fiscal challenges, domestic and external shocks, and projections regarding the time it takes for social sector loans to generate the desired economic, financial, and social results. Also, I agree that if this analysis is properly done, countries would avoid investing in social projects like stadia, that are likely to be underutilized to the point that they become “white elephants.” However, I would argue that there are many pathways to enhancing the productive potential of members of a society that can indirectly impact economic growth. I anchor this argument in the established linkages between economic growth and negative social phenomena such as poverty, crime, violence, and environmental degradation. For example, while the construction of a secure prison may not contribute directly to economic growth, economic growth would be seriously imperiled without it. On the face of it, borrowing for the creation of a semi-professional football league may not be seen as directly contributing to economic growth, except when we consider the economic spin-offs from an increase in the spending power of players, transportation providers, and food vendors, among others.

In all of this, 60 million Frenchmen would find it ironic that IFIs have no problem when private businesses borrow from national insurance schemes but discourage Governments from borrowing for social sector projects that benefit workers and the environment.