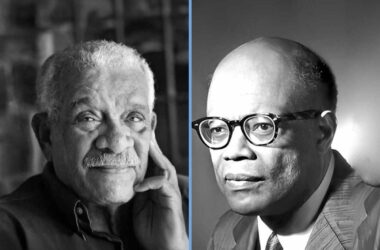

FINDING economic solutions to the developmental challenges of so-called Third World countries was the life-long and celestial vocation of Sir Arthur Lewis, an illustrious son of this soil whose birthday and outstanding achievements are being celebrated this month. Having contributed immensely to the field of labour economics, Sir Arthur was also known for his intellectual tenacity and was aptly nicknamed “Consultant Physician of the Ailing Economics”. Although his various labour-market analyses didn’t exactly deal with retirement economics, I nonetheless shudder to think what the good doctor would have said about the phenomenon (an ailment to some) known in the parlance of economics as the “lump of labour”.

FINDING economic solutions to the developmental challenges of so-called Third World countries was the life-long and celestial vocation of Sir Arthur Lewis, an illustrious son of this soil whose birthday and outstanding achievements are being celebrated this month. Having contributed immensely to the field of labour economics, Sir Arthur was also known for his intellectual tenacity and was aptly nicknamed “Consultant Physician of the Ailing Economics”. Although his various labour-market analyses didn’t exactly deal with retirement economics, I nonetheless shudder to think what the good doctor would have said about the phenomenon (an ailment to some) known in the parlance of economics as the “lump of labour”.

Now for those of us who are not altogether acquainted with this bizarre term, it is the improbable contention that if a group enters the labour market and stays in it beyond their normal retirement date, others will be unable to gain employment. Whether or not this idea is considered a fallacy by many economists today, the fact remains it has been widely discussed in academic circles, albeit without final resolution.

At any rate, the theory of the “lump of labour” has been revisited and expanded to reflect the paradigm shift of the 65+ generation taking on new full-time jobs even when their “real” careers are over. In other words, the workers retire at 65, start to collect their retirement benefits, and then another company hires them – irrespective of the fact that unemployment levels are high and universities are churning out armies of qualified manpower. But whereas dynamic economies like the United States and Germany with their advanced labour markets have the capacity to absorb such potential risks and costs, this development in small fragile countries is bound to create a drag on the labour market – in effect having unintended consequences on the economy in terms of employment, investment and consumption.

So has our labour market been impacted by this trend? Base on anecdotal evidence, I believe it has, if only partially. At a time of high unemployment in Saint Lucia, we have started to witness a phenomenon whereby the older generation refuses to shuffle quietly into retirement – instead opting to pursue a second career by taking on another full-time job, even while receiving reasonably generous pension benefits. Now it would be understandable if a cash-strapped pensioner decided to accept a job in order to bring in needed income or to make up for lost wealth. However, when former highly-paid executives or public servants (often with few or no kids) take on late employment despite receiving generous pension benefits, we need to examine whether this may be distorting the labour market and affecting the chances of the younger generation in getting a foot in the door. From the face of it, I rather suspect that younger workers are already getting the “shorter” end of the stick during this economic slowdown than older ones.

However, let me hasten to add that already, plenty economists have outrightly rejected the notion that stretched-out boomer careers are displacing the younger generation. In fact, research on developed economies show that droves of older workers aren’t to blame for high unemployment. No less an authority than Paul Krugman has deconstructed this argument – skewering the idea and believing it to be one peddled mostly by the economically naïve left. According to Krugman who, like Sir Arthur, is a Nobel-Prize winner: “The “lump-of-labour thinking – and the policy paralysis it encourages – feeds protectionism. If the public no longer believes that the economy can create new jobs, it will demand that we protect old jobs from new competitors…”

Yet, the evidence from various research studies doesn’t always reflect the realities of especially small, vulnerable economies with underdeveloped social welfare systems, weak product and labour markets, sclerotic private sectors and poorly-functioning institutions.

On the other hand, there are economists who share the opinion of Rick Newman, a senior economics writer who has worked for U.S. News & World Report and who covered the 2008 financial meltdown as well as the Great Recession, that “the economy can only support so many jobs, and as older workers stay on the payroll longer, it impedes the creation of new jobs, many of which would go to younger workers. Older people remaining on the job later in life are stealing jobs from young people.”

Of course, I don’t necessarily agree with that crass perspective, but we still do need to know for a fact what impact or profound consequences this trend is having on our resource-constrained society and economy. Needless to say, we cannot just assume that every piece of (one-size-fits-all) research commissioned and carried out in developed countries invariably apply to us, especially given the size and nature of our economy, and our level of development. The same way the presumed consequences of technological progress on employment is still a subject of much heated debate today, we shouldn’t be quick to dismiss any argument as fallacious, in the absence of longitudinal research into our real circumstances. In our own local context, we need to find out whether well-off retirees are in fact restricting job opportunities for younger workers as they stay in the workforce longer.

In some European countries where it has been observed that pensioners don’t always stay retired, governments have instituted measures to deal with the issue by imposing higher taxes on net incomes which exceed a certain threshold after retirement. In other instances, there are regulations which stipulate transition periods of up two years in which elders are obliged to train the junior workforce. Furthermore, working after the retirement age in some developed countries like Germany, even while receiving a comfortable retirement package will affect your social security benefits.

Against the backdrop of high unemployment and fiscal pressures, labour markets have undergone major and frequent changes – and there is no rule that demand one group should make way for another. Saint Lucia saw its own major changes in the labour market in 2015 when the retirement age for the receipt of a full National Insurance pension was increased over a 15 year period from 60 to 65 years. Still, in the current environment of unemployment and low investment, there is an enduring need for small islands like ours to find ways to assess and stabilize their job markets with the support of strong labour-market institutions and (supply-sided) active labour-market policies. We need to find out what’s behind the continued high unemployment – whether it’s really a structural problem, the fault of ill-advised economic policy or the outcome of the changing character of the global business cycle.

For comments, write to ClementSoulage@hotmail.de – Clement Wulf-Soulage is a Management Economist, Published Author and Former University Lecturer.

Always thought that was a really issue in Saint Lucia. Now I am glad that a discerning person has brought it up. There needs to be serious discussion about out retirees and the labour market. Well done Mr. Soulage!

Clement, I am very disappointed with that piece of one sided information you have presented there. Is it true, that retirees at one point was not paying taxes on their investments at age 65 and up? is it also true, that the your tax and send government strip them of that privilege? Why didn’t you offer a reason why these folks are still on the job?In case you pretending not to know: Ins monthly pension cannot cover these folks monthly expenses and your government is now demanding taxes being paid on all rental apartments, rooms and homes at all ages. Clement, with the cost of second hand health care and paying property taxes along with personal taxes on the same property. How do you purpose these retirees cover their backsides. Is back to the job market…..