FOLLOWING the general elections of June 6 this year, we have been caught up in a renewed debate of what the Constitution intends by the phrase “as soon as convenient” as it pertains to the appointment of a Deputy Speaker to the House, and there seems to be no end in sight.

FOLLOWING the general elections of June 6 this year, we have been caught up in a renewed debate of what the Constitution intends by the phrase “as soon as convenient” as it pertains to the appointment of a Deputy Speaker to the House, and there seems to be no end in sight.

While there has been considerable discussion in the press on this, nobody has however explained to us why the Constitution allows just about anyone to be selected as the Speaker of the House but requires that the Deputy be elected from amongst the elected members. It would be interesting to know what purpose this serves, and why the language of the Constitution is such that it allows such differing interpretations of this section.

There is however, another area where our Constitution does not serve us particularly well, and that has to do with the matter of the engagement of the Attorney General.

At Section 71, the Constitution requires the appointment of an Attorney General to be the government’s principal legal adviser, indicating that the office may be either that of a public office or that of a Minister. At Section 61 (2) the Constitution makes the holder of the office of Attorney General a member of Cabinet when that office is a public office, and at Section 30 (3) the Constitution also makes the holder of the office of Attorney General a member of the House when that office is a public office.

Yet, until the impasse with the current Attorney General, few of us were aware of the manner in which the Attorney General was actually appointed. Section 91 (1) of the Constitution specifically removes responsibility for appointment to this position from the Judicial and Legal Services Commission, and, as the office is a public one, then it must fall to the Public Service Commission to make the appointment. No one has however explained how the most senior legal position in our Government is engaged, and we are left to assume that it must be after the Public Service Commission (PSC) has at least consulted, or preferably, obtained the approval of the Judicial and Legal Services Commission.

The difficulty, however, which we now face with the appointment of the current Attorney General rests not only with a candidate’s qualifications and how the appointment is made, but also on the terms of that appointment. Section (5) of the Transitional Provisions contained in the Constitution states that, “until Parliament or the Governor General decides, the office of the Attorney General shall be a public office”. What we do not know though is whether or not the drafters of the Constitution contemplated the possibility of a public office being filled by contract employment.

It makes a difference, as if the concept of “public office” is that of a post filled by a career public officer, one can readily accept that such a person serving in the capacity of Attorney General will discharge his or her functions in the Cabinet of whichever government he/she serves in a purely professional capacity. Professional service is however clouded by contractual employment, particularly considering Section 87 (2) (b) of the Constitution which requires the Public Service Commission to have the approval of the Prime Minister prior to certain senior appointments.

This haziness is compounded by one of the reasons given for contractual employment in the public service, which is that the conditions of engagement are not attractive enough to entice suitable candidates permanently. We regularly see this being played out, notably in the current attempts to engage a DPP where the salary being proposed is far in excess of that contained in the Estimates of Expenditure for this year.

There may be some merit in the suggestion that the difficulty in finding a DPP is associated with concerns related to IMPACS, but only up to a point, as the argument also has merit that changing salary scales in order to attract the “right” person disrupts the entire public service structure. The current proposal for the salary of the DPP will now see the holder of that office receiving far in excess of the base salary of a Judge, according to an advertisement for a High Court Judge appearing in February of this year.

In this current impasse, we have been told for example that the DPP in Anguilla receives a salary of EC $21,000 per month and this may be so, but a 2014 advertisement by the Government of Anguilla indicates a salary of EC $17,500 a month for an Attorney General who will also serve in a role equivalent to that of DPP. According to that advertisement, Anguilla intended to fill two posts for a total less than the sum at which we are being told that one is to be contracted for in St. Lucia.

That salary proposal for the DPP puts upward pressure on the salaries of our judicial officers, and as well on the salaries of other legal officers in the public service. For those of us who wish to point to other territories in the region where the office of DPP also commands super-normal salaries, let them also tell us in the same breath what those countries’ fiscal deficits are, and what their Debt to GDP ratios are. And then explain what has happened to us as a country over the last ten years from the time that we last appointed a DPP. We have to fix our house.

What the current attempts to engage a DPP may be highlighting, however, is an anomaly in the provision of legal services to the country, where, even as the number of lawyers continues to increase, salary demands also increase. This is not what the law of supply and demand teaches, and it may have its roots in another anomaly effected years ago when the Land Registration Act was passed.

Intended to allow the simple identification of parcels of land, ownership thereof and the transfer of title in respect of those parcels, the Act however requires that the transfer be effected in notarial form. This means that a lawyer must prepare a deed, following which a notarial instrument is prepared and taken to the Land Registry to effect the transfer of title. This, of course, is a time consuming and costly process.

In the matter of Desir vs Alcide heard in the Court of Appeal of the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court in 2012, here is what Ag. Justice of Appeal Don Mitchell had to say regarding the transfer of title to land in St. Lucia:

“Although St. Lucia has a Registered Land Act, the legislature has chosen not to include in its provisions the simple process for transfer of title by registration of a transfer form found in other of our islands with the same Act.” (Emphasis mine).

It is time for us to address this anomaly, freeing the legal profession to concentrate on the more pressing matters of justice.

We need also to determine whether appointment of the Attorney General to a “public office” remains relevant today. In our recent past, Attorneys General have been appointed following selection to the Senate, and, whether intended or not, this practice resolves the issue of the hold over of contract employees following elections.

Addressing the issue of how the Attorney General is appointed may require an amendment to the Constitution, and if so, that would then present us with the opportunity to address the appointment of a Deputy Speaker. And if we’re in the process of making these amendments, we might as well set a fixed date for general elections at the same time.

We should all be able to agree on these straightforward changes to our laws and to our Constitution. The more contentious issues requiring change to the Constitution can wait till we catch our breath, but its time to begin to fix our house.

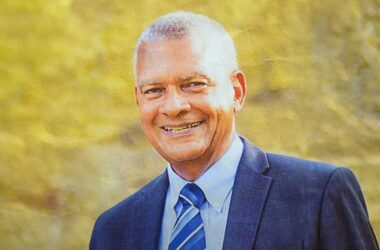

……..missing in action: dr.Anthony;…….three times prime minister;….constitutional lawyer with a phd;…….or,..Should that be WANTED!!