In John Robert Lee’s (JRL’s) ninth collection, “Pierrot”, the Walcottian heron (a brown one) settles near Pierrot who is attending his godmother’s funeral at Choc Cemetery. It then rises into the “beautiful crystal evening-sky over Martinique” with the “white seabird” (p. 72). Pierrot, who does not understand why love seemingly dies, seems to find solace in the thought that death itself will eventually “die”. One reflects here on the Apostle Paul’s conviction “then shall be brought to pass the saying that is written, Death is swallowed up in victory. O death where is thy sting? O grave where is your victory?” (I Cor. 15: 54, 55 KJV).

In this, the very last poem in the collection, John Robert Lee seeks to prefigure the final conquering of Love, Faith and Hope over sadness, anguish and death. Pierrot is transformed from a figure that is the epitome of hopelessness: “how can that love die? How it can go in a hole in Choc cemetery? /And yes, death go die one day”. Much as the French-Bohemian artist Jean-Gaspard Deburau transformed the sensitive and anguished Pierrot of classical literature into a figure capable of rising above tragedy and hopelessness to one exhibiting flashes of confidence and the belief that he is indeed worthy of love, Lee’s Caribbean Pierrot has found Love and its triumph over the harrowing experiences of life. The brown heron and white sea-bird rise together into the crystal evening sky.

And again in “one of us has died, (in memoriam Gandolph St. Clair), Death dies. It becomes an entrance as the drummers/ chant Legba to open the gates, before the lone trumpet/ sounds for the one of us who has died” (p. 43). The ostensible finality of a parting becomes the certainty of triumphant and strident entrance.

This is not simply a collection which contemplates death as, JRL, one of the Caribbean’s most accomplished writers, approaches 70. Nor does it mirror the mildly sombre tenor of Derek Walcott’s White Egrets, its reflections on aging and death regardless. It is a bold exploratory collection of poetry which comes face to face with our mortality and yet hope within the context of a celebration of the beauty of words, easel, camera and sculpture. An aesthetic that is as disconcerting and visceral as it is evocative of the writer’s genius and insightful treatment of the life-themes that thread through this collection.

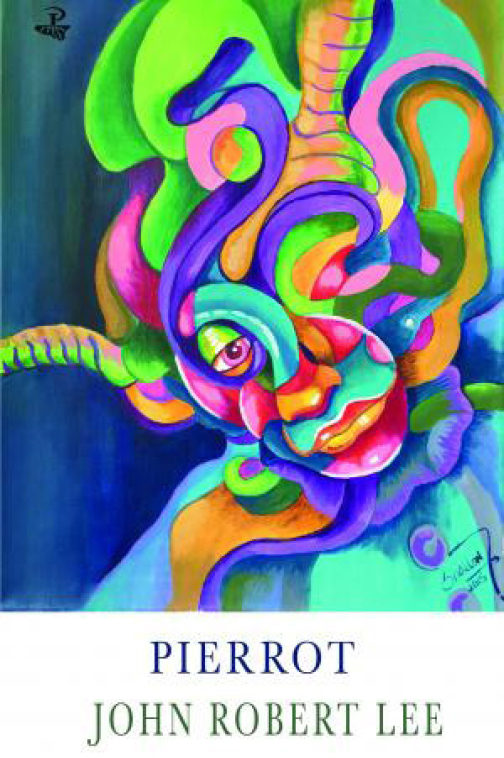

Pierrot does not reflect the haunting gray and white of White Egrets as depicted on the cover of that collection, that singular oeuvre in which Sir Derek “… must make room/ for a shrine [to our artists] before they all die” (White Egrets P. 37). He must erect this shrine to the conscience of a people and the world and do it quickly. Rather, despite the image of the ubiquitous stork which in Walcott’s work is as certain as death, Lee is not panicked. But the rainbow of colour melded into the mask on the cover of Pierrot (art by Shallon Fadlien) seems to send conflicted and conflicting signals. A vibrancy of colour despite eyes of sadness.

In this ekphrastic interpretation of Fadlien’s cover, “at the heart of the mask”, the Pierrot figure, sad fool, jester feigning nonchalance in the Mardi Gras, introduces a surrealism of mood to the collection that is at the same moment desperate and disconcertingly uncanny, earthy and visceral. In Desperate Notes Lee writes, “how come you didn’t know me? /your old dresses made the strips of rags/ busts came from your stained pillow/ …your torn panties covered my crotch. / your bakanal heart make legs/ in front my eyes/ and leave me a damn prancing fool” (p. 52). This is all the more disconcerting because one gets the feeling that the sad eyes of the Shallon Fadlien figure, brooding and gaunt in a mask of psychedelic colour, seems to sharply contrast with the unmasked white face of the traditional Pierrot. It is nonetheless emblematic of the one who broods over unrequited love, yet a brooding that can blossom into an uncharacteristic beauty and colour.

This possibility of beauty and peace is hinted at in the very first poem of the collection, dedicated to local Saint Lucian artist Raphael “Rinvielle” Philip, Pigeon Island. Here, Lee speaks of “[loving] this ascending leaf-strewn way to the curving spine/that leads to musing about angels”. Does the poet find solace here as he comes down from his musing to sit “gazing at the promiscuous surf collapsing forever/all over the wet unyielding stones”? And why are the stones unyielding? This is a reticence rooted in conflicted emotions. The promiscuity of the surf over wet stones bespeaks the consternation of Pierrot over unrequited love.

It is a consternation that is grounded in the real world of apprehension of aging and mortality as seen in Haiku : at 70. “On arthritic spurs/ the aging cock’rel prances/ to the chortling chicks. The mango blossoms/ above its shingled, brown bark…” (P. 44). The real possibility of the blossoming of love out of this uncertainty is palpably addressed in the relatively long ekphrastic poem Song and Symphony: After Shallon Fadlien. “This true story is for you and the unlooked-for-embrace/ in the arms of your tender-hued interest, / which surprised me, coming round this bend, like that arc-en-ciel”. And again: “ …let us hear now the spiraling symphonies/ and songs in chords major and minor, /of our earth’s orchestrated premonitions/ the chastening chords of dark passages, the discordant notes/…the purging interludes of sorrow find their end. /And after, here you are, with patient hand you’ve waited” (Pp 15 & 17). In the movements of song and symphony the discordant notes lead beyond the dark passages of unrequited love to the heart of the matter…love.

The devices that Robert employs to explore the themes of sadness, unrequited love, death and hope are revealing. His “glosa variations” and ekphrastic approaches to a number of pieces of art, poetry, sculpture and photography by artists of local as well as international note and repute are revealing of the poet’s own sightings to which he has come through many meanderings. This collection mediates the poet’s thoughts through the prisms of his life experiences, and the works of poets, writers and artists as varied as Dionne Brand, Francis Thompson, Nobel Laureate Sir Derek Walcott, the calypsonian Shadow, Vladimir Lucien and the photographer Corrie Scott.

In Letter (after Dionne Brand), Lee’s “glosa variation” amplifies the theme of love through faith: “these humble and particular things I know / add thresholds of jalousied doorways I crossed/ pursuing mystery love, drawn even then by echo/ quivering on metronomes of evening softnesses / to find faith waiting in lines of dreadlocked canticles”. Here like in Song & Symphony the theme is mediated through love and music – but also through faith. The theme of faith is ever-present.

The theme of faith-amplified love is seen again in “in the year that Shadow died” (P.54). In that year when JRL turned 70 and received “fewer invitations to read/ my poems of faith/I wish. I wish I could say…I understand my faith companion”. These lines are interesting: there is an old Saint Lucian Kwéyol saying, truism even, “laj ka menen lawézon”, translated “age brings with it, reason” or perhaps “discernment”. Here, the maturing experiences of life lead to a deeper understanding of faith and the discernment of love. The tragic Pierrot-experiences of our lives can be surmounted if one, like the Man of Sorrow, the anti-typical Pierrot, has the faith to transcend them. And this is the lawézon that the poet has come to: “in sight of 70, anticipating retreat, /…beyond my fool heart that loves the slant-eyes of Egypt/ let me not be found among the self-deceiving/ that miss the many-splendoured thing” (Pp. 21-22, After Francis Thompson – A glosa variation). For Pierrot, and indeed for the poet, Faith and Love become indivisible.

In Doors, after photographer Corrie Scott, we exit from the iconic thresholds and past particular lives and remembrances: “Beautiful doors close behind our hearts/ as we step out in weave and tattoos/ name-brand shoes or slippers, tee-shirts and torn jeans/ or coat, tie and lap-top backpack…” and doors represent emblems of once simple lives (P. 40). We step out into the complex and often bewildering negotiation of “…job, church, evening classes or vendor hustle/ to cremations, or beach weddings, or divorce hearings…” (Ibid). And then we retreat to “desperate, faith-filled hopes to which we return/ as to these doors and their certain welcome” (Ibid). And here to seek the solace, the “love after love” of entrances that must surely transcend death and lead to something beyond the “bruised storm-shutters (usually)/ jalousies, cross-hatched lattices…” (P. 39). That something is conceivably that which we closed behind our hearts. Doors here, become a return to and an emblem of hope, faith and love in a personal and particular way.

In Archetypes: After Jallim Eudovic, young Saint Lucian sculptor of international note, the theme of the triumph of Love and its superceding of death is unmistakable, “the first embalming shroud swaddled the first shepherd/ our first love, and we lifted him/ to the first sun of the first hour, every day for nine days of sacred/ remembrance – then the holy mound/ received his sarcophagus, on stretched skins of the first lamb and first leopard”. But what is this ritual, this ancient archetypal image, this symbol of the sarcophagus in which the body is borne into eternity being laid out on the stretched skins of the leopard and the lamb? Are these archetypes of Peace and a dwelling together, a dialectic, a kind of catharsis that moves beyond the trauma, tragedy and desperate notes of today’s living?

The collection, Pierrot, is deep but not obscure. The device of the glosa variation and the approach of the ekphrastic allows us to see through prisms that are as revealing as they are startling. And the language, the phrasing, the imagery is beautiful if often disconcerting: we attempt to see through the myth and the “mystery left to mega-churches and mosques/ wayside shrines and Shaker yards/ vibrating crystals and palm readers” (p. 34). It is surreal and at the same time rooted in the reality of the ground we tread. Haiku at 70 confounds arthritic spurs, prances like the Shadow and gifts us with one of his boldest works yet:

“Learn from the Shadow, solitary, / mighty kaiso griot, how to put the story: / hear in your ear a prancing line/…ricochet and dingolay down the common life you come from/ stand up jumping in the parade of stanzas with your rough voice” – Ars poetica (for Esther Philips, Poet Laureate) (P.69). Rhythmic, earthy, beautiful, the beating wings of a brown heron rising through the clear air over Martinique.

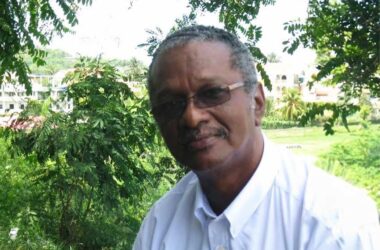

George Goddard is a Saint Lucian writer. In 2016 he published his first collection of poetry, “Interstice”, and is currently working on two other collections. His work has also appeared in BIM: Arts for the 21st Century (2020 & 2019), Interviewing the Caribbean (2020 & 2017), the punch magazine (2018), the Caribbean Writer (2017) and the Missing Slate (2015) among others. Sent Lisi: Poems and Art of Saint Lucia (2014) and Roseau Valley and other poems (2003) are two collections (ed. John Robert Lee et al) which have also featured his writing.