Recent developments in Ethiopia, Sudan, Algeria and Libya have again brought into strong focus the growing need for adequate continental mechanisms to address, reduce and resolve African national and regional conflicts.

The recent early-July twin air-attack on a detention camp for refugees in Libya, the deadly June 22 disturbance in Ethiopia’s Amhara province, plus the new situation in Libya and several other old and new conflicts elsewhere on the continent, have also drawn attention to the workings and effectiveness of the AU’s own crisis response mechanisms.

Under current Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, Ethiopia today boasts the continent’s fastest growing economy — and Africa’s youngest leader, who has become a personal image of the modernist future he wants for his country. Africa’s oldest independent country, it is also the continent’s second most populous after Nigeria, with 102.5 million inhabitants from more than 80 different ethnic groups.

Abiy came to power in 2018, following years of anti-government protests over economic and political issues, led by the Oromo, Ethiopia’s largest ethnic group. He is also the first Oromo to lead the country and has led a remarkable political transformation.

His lifting of an inherited state of emergency, ending a 20-year border conflict with neighbouring Eritrea, removal of bans on opposition political parties, unblocking of hundreds of websites, release of thousands of political prisoners, appointment of the first women as the country’s President and Supreme Court Chief and his promise to open state enterprises (including Ethiopia Airlines) to private investment, have all been positively welcomed at home and abroad.

The Ethiopia leader’s Sudan intervention in mid-June went alongside a separate earlier effort by the African Union (AU) and after a merging of their two proposals as requested by Sudan’s Transitional Military Council (TMC), Khartoum’s largely distant rivals not only resumed talks, but have also been inching closer to agreements on hitherto divisive issues.

Now the two sides in Khartoum have accepted a joint proposal by the AU and Ethiopia that’s resulted in an agreement for a three-year transitional government to be led on the basis of a shared and revolving leadership by the army and civilians.

But the AU recognizes its sloth in addressing crucial matters that necessitate immediate intervention and quick solutions, as in all the cases so far mentioned.

At the 12th Peace and Security Council of African Union (AU) held recently in Morocco, the host country’s minister-delegate in charge of African Cooperation, MohcineJazouli, warned that the reform of the Council “must be guided by fundamental parameters that would have a real impact.”

The continental organization was designed and destined to have lesser bite than originally intended when the pro-colonial independent states overpowered the African nationalist minority at the founding conference of the Organization for African Unity (OAU) in Ethiopia in 1963.

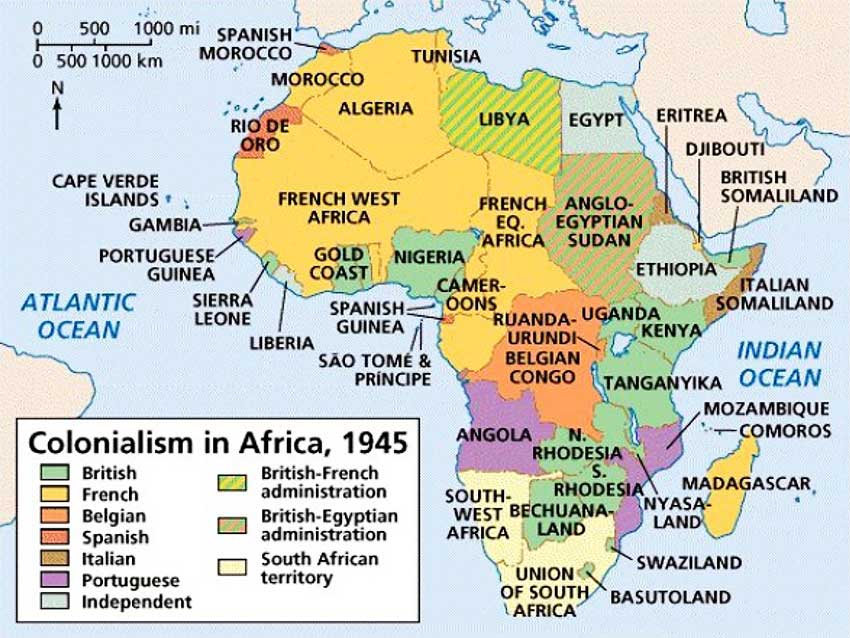

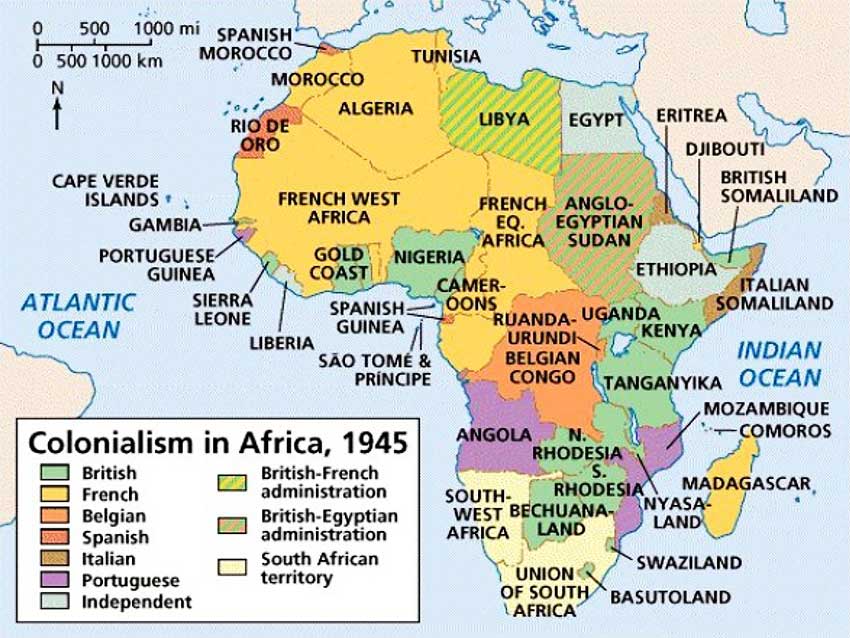

But the unity of Africa’s continental union had been permanently breached much earlier at the Berlin conference of 1884-1885 that regulated European colonization and trade in Africa.

A Union of African States was a short-lived progressive political union of three West African countries in the 1960s — Mali, Ghana and Guinea — led by African revolutionaries like Presidents Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana and SékouTouré of Guinea.

The progressive trend having been defeated at the OAU’s Addis Ababa founding conference, the entity was for many years seen as limping in stride with the former colonial powers, while not doing enough to overcome continental colonial vestiges, eventually being described as a ‘dictators club’.

Following a 1999 resolution adopted in Sirte, Libya (when President Muammar Gadaffi was Chairman), African nations returned to the path of unity at the OAU’s final and the AU’s founding conference in Durban, South Africa, on July 9, 2002, under the chairmanship of President Thabo Mbeki.

But 17 years after its founding conference, the AU continues to grapple with the enormous challenge of serving 55 sovereign states well enough to make meaningful and long-lasting interventions in continental affairs when necessary.

Like with every other like continental entity serving dozens of independent nations, there will always be instances where might will appear to overcome right and politics and economics will override all else.

But Time and History always find ways of reminding the tardy of the need to make careful haste to catch-up with the always-growing expectations of populations moved as much by global trends as by national events – and this might very well be the AU’s time.

THE ROAD AHEAD! Meanwhile, it is to be hoped that the new tri-continental approach to ties between the Caribbean and Africa through Brazil (and The Americas) under the chairmanship of St Vincent and the Grenadine Prime Minister Dr. Ralph Gonsalves opens the way for fluidity between the Caribbean and Africa, which will also have positive implications for advancing the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) request for discussions with Britain and other European Union (EU) member-States on the long-outstanding issue of Reparations for Slavery and Native genocide.