WOULD you forgive someone who recklessly killed your father? How would you regard someone who took your father’s life, the last in his line, just when he was settling down to enjoying his last few years in retirement? What would you say to the insurance agent who tells you that your father had already lived beyond his useful life and that the road accident that caused his death had simply hastened his demise? That the value of your father’s life was zero; that ‘statistically (your) father was dead long before he was killed’?

These are some of the many questions troubling the victim’s son doubling as narrator in this untypical book by quite possibly any Saint Lucian writer.

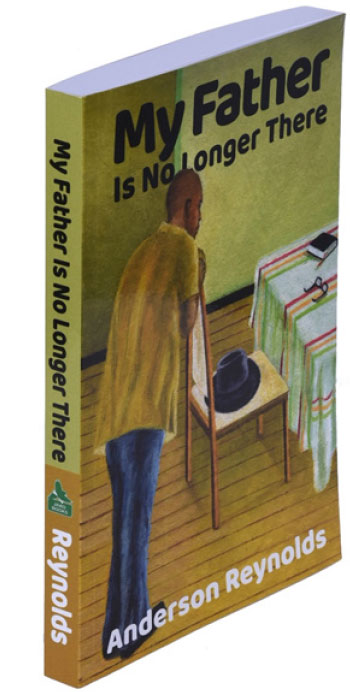

My Father Is No Longer There, like author Anderson Reynolds’ 2017 award-winning novel The Stall Keeper, is set mostly in Vieux Fort, ‘a town at the southernmost tip of Saint Lucia’, in the Caribbean. Appropriately, it is the place of birth of the writer, the place where he grew up and was nurtured by his God fearing, staunch Seventh Day Adventist parents until his mid to late teens (he tendered his resignation from the faith of his parents and family at age 18 years!), the place where he struggled with the very notion of school—until a couple of life-changing developments completely overturned this disposition into a better outlook. Vieux Fort is also the place he returns to after a decade in the USA for an education that circumstances in Saint Lucia could not afford at that time.

From the outset, the writer sets the grim tone of what’s to follow: a seventy-plus-year-old man—his father—is out on his routine morning walk along a driveway a short distance from his home and the public hospital (a leftover of US military-occupied Vieux Fort). A reckless young motorist, as if playing God, as if on a mission with a permit to kill—’And who is this man to be taking lives’ anyway? (pg. 14)—plunges into the septuagenarian father, killing him on the spot.

The riveting narrative portrays the state of mind of the writer/narrator and how he responds: a state of utter disbelief and stubborn denial from the instant the news is conveyed to him till the funeral service and interment and into the days and weeks that follow.

We get insights into the many possible reasons for writing such an account, the most compelling of which being a) to get to know the father better and b) to regain his equilibrium and attain a certain peace that only writing is able to accomplish. ‘My father’s death, the suddenness…the one moment my father was alive…would have to rank high among events that have left a strong and lasting impression upon me…naturally (making it) a candidate for my writing’ (pp. 93-94). Or, it is about bringing closure to the father’s business on earth; ‘to validate my father’s life, to say, “Yes, there was a man called St. Brice Reynolds”’ (pg. 95); to immortalize him even?

My Father Is No Longer There, to be truthful, contains many stories, perhaps many books, within one cover. It’s a book, not only about a revered father’s tragic end but also about his life—the character, his journey, the passions, all that depicts the life, the very essence of the man insofar as the writer can claim to have known him up to that point. It’s a book about family (the Reynolds family)—its composition, modus vivendi, their religious and social values, siblings, individual members’ idiosyncrasies, the apparent contrast between the personalities of husband and wife, what glued them together. By all indications, from the children’s perspective, theirs was a life of work, school, work, school…with ‘very little time to play…our home, our house, was like a factory…It was work, work, and more work’ (pp.145ff)…like we were the children of Israel under forced labor…’(pg. 92).

As if that is not enough, My Father Is No Longer There is also a book about the writer—his infancy (hugely affected adversely by the temporary separation from his mother); growing up in an environment forbidden to merge with his peers and the rest of the community because of religious restrictions; his ‘maladjusted’ childhood;his decade-long sojourn in the USA where he really confronted his demons, coming into a better understanding of self, history and culture, emerging a different, more integrated person (a metamorphosis really).

Unsurprisingly, after his father’s death, more than ever before, with a high level of modern education, he admits that he no longer subscribes to the ‘faith theories’ of the father: ‘My father’s godliness…couldn’t save him from the reckless twenty-four-year-old who took his life…(Now) I believe who lives, who dies…has little to do with good or evil, but with effort…’ In this pulsating narrative at this point in the account, the reader will be shocked at the number of personal details about his life the writer dares to share. It must have taken a great deal of courage for such intimate disclosures. Consider the statement: ‘…given my childhood history of retarded, maladjusted and antisocial behavior…’ (pg. 92). But then a writer is only worth his salt to the extent he’s willing and unafraid and unashamed to be honest with his readers.

In the continuing effort to uncover who his father was in fact—’not the man knocked down on the side of the road like a useless paper doll’ (pg. 17); not ‘the man lying (in a coffin) dressed for a wedding that would never take place’ (pg. 6); nor the man the writer laments he could never come close to emulating (pp. 35-39)—and to present that image to the reader, Reynolds devotes at least one entire, long chapter, ‘My Father Was A Beekeeper’ (pp. 188-205), to the one passion that his father loved above all his other occupations. At times one may complain that the ‘treatise’ entertains too much detail, goes on for too long; yet the father’s ‘lecture’ on the way of the bees is so packed with instructions for life that that criticism is soon withdrawn. By the author’s account, it appears that the older Reynolds applied the lessons learned from observing the bee colony toward the disciplining and upbringing of his brood: ‘My father always lectured us on helping each other, sticking by each other, protecting each other….’(pg. 201)—distinctive features of a thriving bee colony.

According to the author, the two episodes that best represent the man his father was are the brother’s—’the one who’s a university professor’—eulogy and his own tribute poem at the funeral service. The images portray the man they both knew as opposed to all others of him in a state of rigor mortis on a cold hospital slab, or in the mortuary prior to post mortem or lying still and helpless in a measured casket.

Despite the tone of sadness and utter loss that colours the first pages of the book, My Father Is No Longer There is decidedly not all doom and gloom, not exclusively death-focused. It offers glimpses of a typical ’60s Saint Lucian family’s path toward self-growth and social progress—industriousness, working the land or at a trade like tailoring, or for those able, a trip to the UK; it demonstrates that even in the most apparently perfect family there are issues of pain and sorrow, of sacrifice, of sweat and tears, of petty familial squabbles, of moments of celebration and of joy and laughter; to the reader less familiar with the backdrop against which the story is written, it gives a bird’s-eye view (almost cinematic) of large parts of the country as narrator drives home from the other extreme end of the country—deliberately unhurried—to confront the harsh reality of his father’s death (pp. 121-140 – ‘A Rendezvous With Death’).

Another thing: this is not fantasy, not fiction. Every bit is factual and historically verifiable—except where the writer strays (a rarity) and enters the realm of speculation.

In retrospect, Reynolds tells us ‘the possibility and hence fear of my parents dying had been a preoccupation since childhood’—no doubt brought on by the intense insecurity the infant Reynolds experienced due to the father’s absence and later the mother’s departure for England—however, ‘I can never get used to the notion…although ‘ Now I have a better appreciation…that fathers are irreplaceable…I cannot overcome the fact that my father is no longer there’. Hence, ‘Tell them I want my father back’ (pg. 186).

The side attractions notwithstanding, My Father Is No Longer There does succeed in the portrayal of the devastating impact of a father’s tragic, untimely death on a son. It does seem a bit strange though, doesn’t it, that given the writer’s acceptance of the imminence (pg. 179) and immanence of death as attested to in his eulogistic poem—‘I know, Death,…/ both of us know that / life and Death are the same…’ (pg. 180)—he is unyielding to the fact of the loss?

The death of a loved one is nothing new, nothing unfamiliar. It’s how the story is told, and the other inside glimpses of a family in motion, that makes this one so compellingly readable.

Do I still hear someone asking, ‘But who was my father?’

My Father Is No Longer There(215 pp) is published by Jako Books, USA, listed price US$24.95, but in St. Lucia it is sold for EC$60. It is available online at amazon.com both in print and as eBook. In St. Lucia it is available at T&M Toy Stationary (JQ Plaza, Vieux Fort), Glo-Mart (Gablewoods South), Best of St. Lucia & Noah Arcade (Hewanorra International Airport), and AF Valmont (Laborie Street, Castries).

![Simón Bolívar - Liberator of the Americas [Photo credit: Venezuelan Embassy]](https://thevoiceslu.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Simon-Bolivar-feat-2-380x250.jpg)