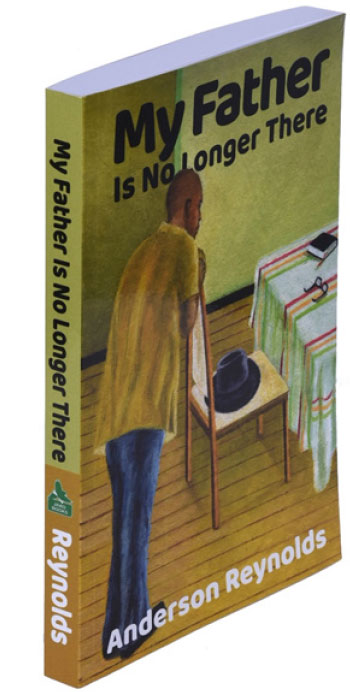

It took me a day or two before I made the time to sit down at my laptop, and begin reading Anderson Reynold’s latest book, My Father Is No Longer There.

Two hours later, I got out my phone and sent Anderson a Whatsapp message:

“Reading My Father. In one breath. I’m at page 63 now and he is gradually emerging, like a man walking towards me from a long distance. The book is a love ballad, Anderson. And the language so much more beautiful than anything of yours I have read before. Strong, supple and sensitive at once. I cried at one scene.”

The next day, I rushed around to get my work done, just to get home and back to the book. “I stayed up till midnight to read. Have just a little left now. Dreamed about it all night.”

The book that starts out as something I can only describe as a love ballad – odd as that word may sound when used to describe the relationship between a grown man and his deceased father – takes an unexpectedly desolate turn, just a few chapters later. Just when you’ve settled in to what appears to be the fabric of the memoir and the pattern of the story: a father tragically killed in old age, his adult son trying to come to grips with the trauma of that loss and, in doing so, weaving the narrative of his entire family’s history as Seventh Day Adventists in Vieux Fort during the 1950s, 60s and 70s, the author suddenly shifts gears and the story takes an entirely more personal turn still.

The revelations that follow are unusual, not just in Caribbean literature, but in Caribbean social science as well. As a social historian myself, in all my reading on West Indian household labour strategies, I do not recall ever seeing anything that comes close to this testimony about the impact of (return) labour migration on the emotional well-being of the children left behind in the care of grandparents, aunts and others.

In Anderson’s hands, the trauma of his father’s death, one wet morning in June 2002, when a speeding driver lost control and hit him during his early morning walk, now becomes the touchstone for that much earlier trauma experienced when he was just a toddler: the temporary loss of his mother to the migrant stream that took tens of thousands of aspiring West Indian men and women to the United Kingdom, in the late 1950s and early ‘60s.

Much has been written about the social, economic and political aspects of West Indian labour migration over the years, but the crushing emotional impact it – occasionally – must have had, remains virtually invisible in both academic works and Caribbean literature. From my own work on intergenerational relations in Vieux Fort since 1910, I can testify to the profound long-term impact of the quality of emotional relationships between children and their care-givers on those children’s future social, economic (financial) and educational development.

In Anderson’s own case, his family’s strong love and work ethics and, especially, his mother’s indomitable educational aspirations for her children did not save him from the long-term emotional trauma of that early childhood separation. But it did, however, help to keep him sufficiently focussed to eventually be able to come through the emotional catharsis that followed, and out the other end of that long, dark tunnel of depression… and emerge as an accomplished author and analyst.

The two stories of trauma – his father’s death and his own early childhood anguish – thus become entangled in each other, are reflected in one another, creating contrast, depth, and perspective, like two hands playing the piano, like an image bouncing back between two mirrors, or like two birds struggling around each other in mid air.

My Father is No Longer There is a biography and an autobiography, as well as an important addition to our understanding of the unwitting impact of West Indian migration on the psyche of the children involved.

The background to the story is that of a pastoral Caribbean childhood, a joy to read and a feast of recognition to anyone who is familiar with this slice of time and space, the shape and colour of it, the smell, the flavour, the colours, and the characters.

The language used to tell the story is very much Anderson’s own: verbal, direct, unadorned, its power derived sometimes from simple repetition, sometimes from raw dialect. What it lacks in finesse and grace, it makes up for in honesty, integrity and sheer forcefulness.

But to me, the overwhelming power of this book lies in the author’s inestimable courage, his willingness to explore, bare and share a deeply intimate side of himself to us, his readers. Because of this, reading My Father Is No Longer There is a privilege to be savoured, and one that ought to be treated with the respect it deserves.

Editor’s note: Originally from the Netherlands, but residing in Vieux Fort, St Lucia, Dr Jolien Harmsen is a social historian and the author of three books including Sugar, Slavery and Settlement: A social history of Vieux Fort, St Lucia, from the Amerindians to the present (1999); Rum Justice (novel, 2007), and a History of St Lucia (2012). Dr Harmsen and Dr Reynolds are regarded as the two foremost authorities on the socioeconomic history of Vieux Fort.

![Simón Bolívar - Liberator of the Americas [Photo credit: Venezuelan Embassy]](https://thevoiceslu.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Simon-Bolivar-feat-2-380x250.jpg)