“It would have been heart-rending for McIntyre in his twilight years to watch the regional integration project pause and even reverse. In company with Ramphal, William Demas and political personages such as Jamaica’s P.J. Patterson, Barbados’ Sir Henry Forde and later Owen Arthur, he had helped to construct the foundations for a Caribbean Single Market and Economy (CSME) and had proposed reasoned solutions to the problems of implementing regional decisions.”

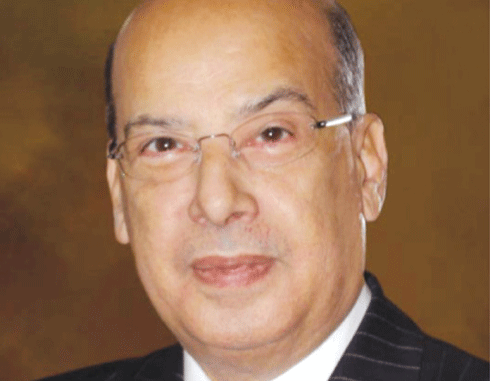

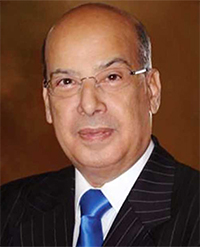

Sir Meredith Alister McIntyre was born in Grenada but for much of his life, dedicated to promoting the interests of the Caribbean, few knew his birth place. What they knew was that he belonged to a group of West Indian thinkers whose identity was West Indian and who worked assiduously in the collective interest of the region.

Since his passing, Caribbean people have heard many well-deserved tributes to him, each recounting aspects of his life that had a common theme – his deep commitment to the Caribbean region.

From the 1970s, there was hardly any significant event in the trade, finance and international political experience of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) in which Alister McIntyre was not an active participant.

Among his many contributions, there are four specific areas that have left an indelible mark on the region’s development. These are: his work as part of the technical support team for the Caribbean negotiators of the 1975 Lomé Convention, the first aid, trade and investment agreement between the European Economic Community (EEC) and the African Caribbean and Pacific Group, his participation as a Commissioner in the historic West Indian Commission (1990-1992) and in the Caribbean Regional Negotiating Machinery; his stewardship of the CARICOM Secretariat as its second Secretary-General (1974-77); and his role as Vice Chancellor of the University of the West Indies (1988-1998).

Sir Alister had the dubious distinction of being the only CARICOM Secretary-General under whose tenure, from 1974 to 1977, no Heads of Government meeting was held. Disagreement between Trinidad and Tobago’s Eric Williams on the one hand and Guyana’s Forbes Burnham and Jamaica’s Michael Manley on the other, militated against meetings.

Notwithstanding no meeting of the Caribbean leaders, McIntyre held CARICOM together through Ministerial meetings. While others were staying away from the Caribbean house, he kept the lights shining brightly.

In his tribute to Sir Alister, Sir Shridath Ramphal – a close friend and intellectual collaborator with McIntyre in the cause of Caribbean integration – remarked, “he had devoted his life to Caribbean unity and was already, as he went, worrying over the darkening of the regional scene that threatens”.

It would have been heart-rending for McIntyre in his twilight years to watch the regional integration project pause and even reverse. In company with Ramphal, William Demas (another iconic Caribbean figure) and political personages such as Jamaica’s P.J. Patterson, Barbados’ Sir Henry Forde and later Owen Arthur, he had helped to construct the foundations for a Caribbean Single Market and Economy (CSME) and had proposed reasoned solutions to the problems of implementing regional decisions.

During the short period of his Secretary-Generalship of CARICOM, McIntyre had proposed the establishment of a Caribbean Commission that would comprise a high-powered trio who would implement the decisions of heads of government – something, which for the most part, fell through the cracks in the Secretariat for lack of executive authority and resources. His idea was developed by the West Indian Commission on which he served with Ramphal (as Chairman), William Demas and ten other West Indians, distinguished in their fields.

The idea, as Ramphal described it in his memoir (Glimpses of a Global Life) was to establish “a small group of some of our best people drawn preferably from public and political life, engaged upon that task of making regional things happen and making things happen regionally”. While heads of government accepted many of the West Indian Commission’s recommendations, contained in the seminal report entitled Time for Action, they rejected the notion of a Caribbean Commission. In the result, the deficit in implementing decisions of CARICOM remain large, causing one of the greatest criticisms of the regional integration project.

The Caribbean Single Market and Economy (CSME), another of the proposals of West Indian Commission, did come into being 14 years after it was recommended. At a heads of government meeting in Jamaica in 2006 under P.J. Patterson’s leadership, the CSME was launched to provide the foundation from which Caribbean countries and Caribbean companies could become globally competitive and capitalize on opportunities for market access that could be delivered by joint bargaining with other countries and regions.

P.J. Patterson exhorted the gathering of all CARICOM countries at the highest levels “never to abandon that passionate commitment to the full advancement of the region which has allowed us to fulfil this part of the dream today”. Five years afterwards, at a Retreat in Guyana in 2011, the Heads decided to “pause” the single economy process – a decision that the Prime Minister of St Vincent and the Grenadines, Ralph Gonsalves, described in a letter to the Secretary-General as “sliding backwards” in a dynamic world. Alister McIntyre must have wept, witnessing the dissipation of his labours and that of his fellow West Indian visionaries.

Fortunately, with the advent of Mia Mottley’s leadership, as Prime Minister of Barbados with lead responsibility among CARICOM heads of government for CSME, energy and resolve have returned to the process.

McIntyre knew from experience learned in the front line of regional bargaining, that, as small states, Caribbean countries need to pool their resources in order to be recognised in the global arena and to give themselves the chance for effective negotiation with countries more powerful than they are. He also knew that it was harmonisation of foreign trade policies (and its international politics) by CARICOM countries that allowed Ramphal and Patterson, backed by technical experts such as he, Demas Frank Francis (Jamaica) and O’Neil Lewis (Trinidad and Tobago), to negotiate the best trade, aid and investment deal that the Caribbean has ever achieved – the Lomé Convention with the then EEC.

Division within CARICOM on external issues, such as the current failure at the Organisation of American States to sustain a regional identity from which the strength of CARICOM countries derive, would have disappointed McIntyre. He acknowledged that CARICOM is a community of sovereign states, but he also knew that the exercise of individual state sovereignty in alliances with countries outside the Caribbean, weakens the region and, eventually, each state. His credo was: “We do it better when we do it together”.

His ideals will live on and they will be kept alive, because they are right, sensible and, in the end, in the region’s interest.

Editor’s note: The writer is Ambassador of Antigua and Barbuda to the United States and the Organisation of American States. He is also a Senior Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies at the University of London and at Massey College in the University of Toronto.