The Language Gets Its Day

INTRODUCTION

THE kwéyòl language is the thread which weaves through all aspects of St. Lucia’s oral traditions: traditional drama, music, dance, social life. Apart from its own value as a symbol of identity and culture, the language effectively facilitates the passing on of oral traditions, be it forms of folk expression in song, dance and music or forms of economic and social activity.

Kwéyòl, the Saint Lucian creole language, is the focus of the observance of Jounen Kweyol (International Creole Day) on October 28 each year. This occasion is observed by creole-speaking peoples throughout the world grouped into an international organization called Bannzil Kweyol.

While a specific date had been designated, members of Bannzil found it more practical and convenient to organize activities on dates close to the designated date where socio-political realities did not permit mass gatherings on October 28.

JOUNEN KWEYOL

For over three decades, Jounen Kweyol has been observed in St. Lucia with a very significant level of public participation. In structure, the Jounen Kwéyòl programme, when it first began, did not reflect much of a departure from other quasi-national public events. However, the specific, sustained thrust towards making a strong statement on culture and the unique organization of content, folk song, dance, and socio- economic activity has made the now-national Jounen Kweyol different from other similar activities.

In its first years, Jounen Kweyol was organized with the participation of a number of non-governmental organizations. The collaboration of two NGOs, namely the National Research and Development Foundation (NRDF) and the Folk Research Centre (FRC), with Mouvman Kweyol Sent Lisi (MOKWEYOL) made the event more than just a narrow, “cultural” show but attempted to fit the kweyol language and culture and what it represents into a developmental perspective. The parental relationship between FRC and NRDF, on the one hand, and MOKWEYOL on the other hand, contributed to the progressive development and the concept and manifestation of JounenKweyol as a national event.

The following examines the first years of JounenKwéyòl in 1983, 1984 and 1985, and provides a record of what has become arguably the major national participatory and celebratory event in Saint Lucia.

1983 – The Beginning

The major focus of the observance in 1983 was radio. The day was observed with almost fifteen hours of Kwéyòl broadcasting on the national radio station, Radio St. Lucia. This was a historic day which will be remembered by many St. Lucians. From eight o’clock in the morning, kwéyòl music was played. There were a number of special features, including an interview with Earl Huntley, who had conceived and created the popular kweyol programme, “Radio-a se sanou.” The host of that programme was Sam ‘Juke Bois’ Flood, who is still hosting kweyol programmes. There was also a special feature on local poets who have produced work in Kweyol. The major news events for that day were reported in kweyol.

The highlight of the broadcast was a two-hour link-up with DBS radio in Dominica. During that period, persons involved in promoting kwéyòl in Dominica and St. Lucia exchanged views on topics such as the role of the Kweyol language, BANNZIL, kwéyòl drama and attitudes towards the language. Among the persons who were on air for that special programme were Yves Renard, PearletteLouisy (now St. Lucia’s Governor General), Allan Weekes and broadcaster Marcellus Miller. On the line from Dominica were Alwin Bully, Felix Henderson and SinkyRabess. For the entire day, Radio St. Lucia’s broadcast was flavoured with kwéyòl music.

Jounen Kwéyòl was also observed independently in two communities. A panel discussion was held in Laborie where the role and importance of Kwéyòl as a language was examined. This discussion was well attended and there was a lively exchange of views between the panelists and the persons within the community.

The Fond Assau Combined School had its morning assembly in Kwéyòl. In the afternoon, students of that school, directed by Michael Gaspard, presented a cultural show in Kwéyòl. The school principal and other teachers participated in the programme.

The radio link-up which was organized in cooperation with the local station was not direct line link-up, in that both stations monitored each other off-air (on their respective frequencies) and agreed on a cue word to switch to each other. It was a process which lacked technical sophistication but did not affect the quality of content and historical importance of the occasion.

The programme for JounenKwéyòl was coordinated by MouvmanKwéyòl Sent Lisi operating out of one of its parent bodies, NRDF.

Mon Repos, 1984

The observance in 1984 marked the introduction of mass participation in the observance at the community level. The first creole community day was held in Mon Repos, a small community on the east coast. After months of preparation, including meetings in Mon Repos with the recently-established ‘ganykwéyòl’ (creole group) there, the programme was organized.

The day began with a Kwéyòl mass celebrated by Fr. Patrick Anthony, an ardent Kwéyòl campaigner and founder of the Folk Research Centre. Amidst the punctuation of Kwéyòl hymns, Kwéyòl intersession and prayers, his message was one of undiluted support for the language. In his sermon, Fr. Anthony emphasized the need for cooperation in the restoration of the aspects of St. Lucian culture whose existence is threatened by external influences. The honouring of Sesenne Descartes, a St. Lucian chantwèl from Mon Repos (now recognized as Dame Sesenne Descartes, Queen of Folk) which followed the mass was a precedent set. In later years, other folk heroes were recognized. Sesenne received a certificate inscribed in Kwéyòl, a trophy, flowers and numerous words and songs of praise. She, in turn, gave thanks in song with the rendition of “Manmay la di way” which has become one of St. Lucia’s classic folk songs.

For the rest of the day (Sunday, October 28, 1984), the atmosphere and mood was ‘kwéyòl’. It was a magnetic rallying theme for the St. Lucians who came from all over the island to witness the event. There were creole meals served in creole vessels, creole games, including walaba (a unique St. Lucian version of cricket), and creole toys such as wawa symbolizing the deep Christian influence on creole culture.

The other folklore legends who joined Sesenne in sharing with the people the richness of St. Lucia’s oral traditions were the late Eric Adley, Rameau Poleon and his MorneGallian Band from the south of St. Lucia, Leonards John and Clifton Joseph, together with a group of folk dancers and singers from Piaye on the south west coast.

The participation of more youthful groups from Au Leon, Fond Assau and the LapoKabwit drummers from Castries added to the experience.

The other activities for that day included the sale of literature on Kwéyòl, including the bilingual newspaper, BALATA, and a creole dance featuring kwadril groups from Mon Repos, Vieux Fort and Castries.

In her reflection on the event, Armelle Mathurin, leader of the Kwéyòl group in Mon Repos, noted, “The strictly creole meals served in creole vessels, the fun and laughter, the entertainment, the warm and heartfelt St. Lucian greetings, the general atmosphere was all fitting to, and expressive of, the day and the extent to which our people are still true to their own national culture.

As far as the organization and planning for the culmination of JounenKwéyòl at Mon Repos was concerned, there was much scope for expansion and Mon Repos would not mind another opportunity to improve and prove itself in that area. In the first instance, the planners never in their wildest imagination anticipated such a crowd and, therefore, preparations were somewhat limited in all areas, including the numbers of hands running and manning the day.

But thanks again to the “koudmen” spirit which is still very prevalent in St. Lucia, the day was saved by the additional service of voluntary helpers who came in at the twelfth hour. Although unwritten, thematically, the day in Mon Repos reflected the value and strength of the Kwéyòl language.

Radio played an important role. The cooperation of Radio St. Lucia in facilitating the numerous programmes and information and education features assisted in the process of mobilizing people for participation in the Mon Repos Creole Day. Numerous announcements encouraging St. Lucians to hold conversations and communicate in Kwéyòl, on the two days preceding October 28, were patterned on the adopted slogan “Di’yanKwéyòl” (say it in Kwéyòl.)

There was a very high percentage of Kwéyòl language programmes on creole music information from other countries involved in the global creole movement. Also broadcasted was general information on JounenKwéyòl activities in St. Lucia, Dominica and other Bannzil members.

A Kwéyòl language announcer worked alongside an English language counterpart for the entire day, starting with “Bonjou Sent Lisyen, jòdiséJounenKwéyòl” at 5.30 a.m. sign-on time. The hourly news bulletins were done in Kwéyòl and English, giving adequate evidence of the MOKWÉYÒL position that St. Lucia is a bilingual society and the languages must function side by side.

The major local news bulletin was done in English and Kwéyòl and throughout the day, folk music, kadans and other forms of music associated with creole folk dominated the airwaves.

The two-hour radio link-up was the highlight of the use of mass media in JounenKwéyòl. Apart from the discussants and announcer in the studios of RSL and DBS, a member of GEREC (a Creole studies group in Martinique and Guadeloupe) in Martinique joined on air by telephone. The two-hour exercise involved news presentations from Dominica and St. Lucia, music, short features and general exchange of ideas on work in progress.

October 27 reflected similar thrust in programming with “misiktipik”, the music of the rural folk, features and a 90-minute radio call-in discussion examining research and promotion of the Kwéyòl language. This session offered the public the opportunity for feedback on the positive and negative opinions of creole. Inevitably, the arguments for and against the wider use of the language in the society were prominent. It was noted that the reasons given for the positions had not changed significantly over the years.

Reporting to a national consultation in St. Lucia in 1980, Lawrence Carrington captured the entire situation: The problem with non-acceptance of Creole goes beyond failure to capitalize on the major communication medium; it extends to non-acceptance of creole speakers. Persons whose societal functioning is circumscribed by lack of competence in English evaluate themselves in terms which reduce their ability for self-fulfilment.

Fond Assau, 1985

The activities organized as part of the Creole Community Day in Fond Assau in the north-east of St. Lucia, in October 1985 reflected the development of the concept of JounenKwéyòl and a further popularization of the occasion. Like Mon Repos, which was the home of one of the island’s leading chantwèls, Fond Assau had its own cultural and historical importance. Fond Assau is the home of surviving generations of the giné, one of the African tribes whose cultural and social practices were to paint the St. Lucian cultural landscape. Reference is made here specifically to the kélé, a religious sacrificial ritual which was still practiced at that time in that community.

The other precedents set by the Fond Assau observance were:

(a) The use of the theme “Kwéyòl – An Lang, An Pèp, An MòdLavi” (Kwéyòl – a Language, a People, a Way of Life) as a rallying point for the community and MOKWÉYÒL.

(b) The involvement and early sensitization of community groups: GanyKwéyòl Fond Assau, Fond Assau Youth Development Organisation (FAYDO), the Prayer Group, TjèKanpèch (youth), Mothers and Fathers Groups of Fond Assau, and Chassin, a nearby community.

The selection of the theme helped broaden the perceptions of St. Lucians of the role of Kwéyòl in St. Lucian culture. It also moved the discussion on Kwéyòl from the usual narrow confines of linguistics and communication. This theme was the rationale for the content of a souvenir booklet commemorating the occasion – stories of the expression of folk culture through La Wòz, the manifestation of creole life through portrayals of creole medicine and farine making.

In a foreword to the book, MOKWÉYÒL President, PearletteLouisy stated: “Kilti yon pèpsélispwi’ysé lam-tisémannyè’ykaviv, mannyè’yka pale, mannyè’ykaèsplitjékò’y. Noupèp Sent Lisyenkavivankwéyòl, nouka pale an langkwéyòl. Lang kwéyòlséwasinpèp la, sé lam nou, sémanyèpensénou.Médélè I nitèlmanbagaykikamennasékiltisa la noukaoblijémandékonouchèsyon. Ki sakikawivékwéyòl la? Eskitouswit, noukatouvaykònoukon yon pèp san lam.Eskikiltinouaséenportanpounou, pou nous a fèmannivpousapwèsévé’y?”

By extension, the involvement of a number of community groups in the planning and implementation of the programme has a number of lessons. This level of involvement not only legitimizes the role of the Kwéyòl language but also the value and function of creole practices and habits. The report of the Planning Committee in Fond Assau highlights the extent of organization and also the role of commitment to the preservation of the oral traditions.

The report states: “Planning an event of this nature was not an easy task and, as a result, letters were sent out to the various groups in the community — such as the Fond Assau Mothers and Fathers Group, the Chassin Mothers and Fathers Group, Fond Assau Youth and Cultural Organisation (FAYDO), the TjèKanpech, Prayer Group and individuals who were very much involved in preservation and development of Kwéyòl.”

A Planning Committee was formed and responsibilities were given to these persons on the committee. In the beginning, the enthusiasm was not evident; therefore, a film on the Mon Repos JounenKwéyòl was shown to influence the people. Each committee had its duty to perform – one took care of exhibitions, another organized the church service, another oversaw games, and a special working committee was assigned the making of farine, sawing wood, loading donkeys, etc. The amusement committee was mainly responsible for solo, kont, quadrille, débòt, bèlè, La Rose and La Marguerite. Then there was the eats and drinks committee, which made a total of seven committees.

As was the case with Mon Repos, the day started with a creole mass celebrated by Fr. Reginald John, a Catholic priest (now deceased) whose involvement in the promotion of Kwéyòl preceded all the formal activities of MOKWÉYÒL.

Hymns, lessons and intercessions all scripted in Kwéyòl provided the preface for the sermon which was highly supportive of the creole way of life.

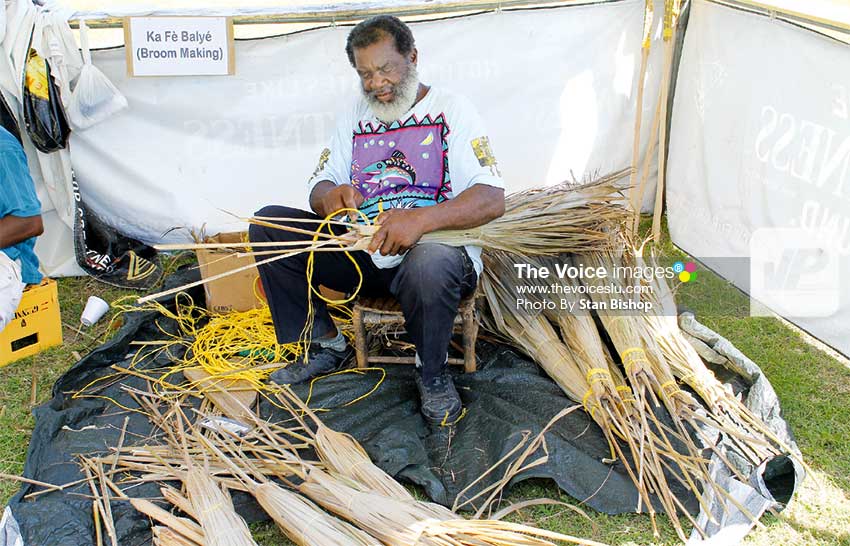

Throughout the day, there were live demonstrations of economic activities associated with creole folk, such as wood sawing (siay), farine making, preparation and sale of various types of creole food, and preparation of creole and herbal medicines. There was also an exhibition of household items, clothing and other general utensils used by the rural folk – calabash bowls and goblets, tin kerosene lamps, crab traps, ‘katwiban’ (underpants), straw chairs, baskets and tea mixers/swizzles (lélé).

The extension of the programme to honour persons in the community who have contributed to the way of life of that community was significant. Six persons were honoured for their roles in promoting folk expression, music, traditional medicine and economic activity. Those honoured were:

1. Norris Lionel – WimèdKwéyòl (Herbal Medicine)

2. OctavieJacobie – FanmChay (Midwife)

3. Lawrence Clifton – Siay (Wood Sawing)

4. Hamilton “Slim” St. Ange – Kontè (Storytelling)

5. Michael Delaire – Kélé

6. Sparrow – Mizik (Music)

The cultural presentation again illustrated the variety of forms present in St. Lucian folklore. The groups and individuals who performed in Mon Repos were joined by a La Marguerite group and masquerade band. Sesenne Descartes, who formally opened the exhibition, was part of the Mon Repos group. A notable exception at the JounenKwéyòl in Fond Assau and Mon Repos was Florita Marquis, St. Lucian chantwèl and folklorist from Canaries, a west coast village. Marquis’ participation could have injected a distinct flavour to the occasion.

The predominance of adults and older folk in the activities attests to the strong commitment to appreciating and guarding St. Lucia’s oral traditions. This, however, has not erased the stigma associated with folk performances. Mass media and the education system continue to portray the value of folklore strictly in terms of its relevance to the perceived limitation of the unsophisticated lifestyles of rural folk. Thus, the survival of these oral traditions will depend much on change within the traditional roles of media and formal education.

Radio again played an important supporting role. On Monday, October 28, 1985, the two-hour link-up with DBS (Dominica) provided the main forum for discussion and information-sharing. The local discussants were members of the MOKWÉYÒL Central Committee with a member of the Fond Assau Planning Committee providing the community perspective.

A radio discussion and call-in programme on Saturday, October 26 had the effect of the previous year. Coming out of the discussion was a clearer definition of the concept of kwéyòl as a way of life. A television broadcast of a short feature on the Mon Repos event stimulated public interest. However, there was a significant drop in total hour broadcast from 44% in 1984 to 23% in 1985.

One new dimension in the 1985 observance was the general programme organization under the auspices of the Folk Research Centre. Co-ordination shifted from the National Research and Development Foundation. Unlike the NRDF which addressed the physical and infrastructural aspects of development, FRC’s mandate directs it to cultural research and development. The guiding principles of the FRC are summarized in its objective to develop the St. Lucian people through “Promoting the use of folk arts as a weapon for change and integral development” and “Promoting the use and appreciation of Kwéyòl as a vital force in the process of liberation.”

Jounen Kwéyòl was thus integrated into a programme of the FRC, and gave the celebration stronger organizational support and relevance. Fond Assau thus marked a significant movement.

CONCLUSION

The early observances of Jounen Kwéyòl in St. Lucia in 1983, 1984 and 1985 illustrated the popularity of the language and its culture. It also highlighted the high level of ignorance about St. Lucian oral traditions by St. Lucians.

This conclusion was arrived at based on numerous questions asked during JounenKwéyòl activities. While increasing popular support was observed, the accompanying cultural events lacked public participation. In those years, constraints of space at Mon Repos and Fond Assau were responsible. However, the question regarding the general attitude towards folk forms as show pieces remained.

[This article is adapted from “Oral Traditions in St. Lucia: Mobilisation of Public Support – JounenKweyol”, by Embert Charles. In Research in Ethnography and Ethnohistory of St. Lucia: A preliminary report. Edited by Manfred Kremser and Karl R. Wernhart. 1986.

Charles was the first Executive Director of the Folk Research Centre. He has since served as St. Lucia’s Director of Information Services and CEO of ECTEL, which is responsible for telecommunications development in the OECS.]