George Goddard is a Saint Lucian writer. His reviews and poems have appeared in several on-line and print journals and anthologies in the Caribbean, Europe and India. His collection of poems Interstice was published in Saint Lucia in 2016. He writes in both Saint Lucian Kwéyòl and English.

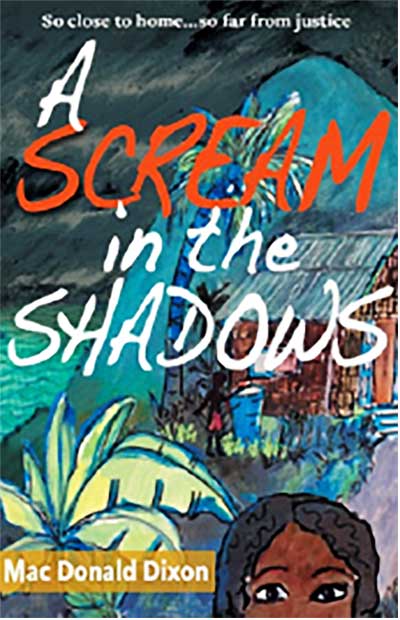

Arguably one of the Caribbean’s most versatile writers Mac Donald Dixon, in his third novel, A Scream in the Shadows (Papillote Press, 2022), has chosen to craft another work, in what has become his signature approach of grounding his story-telling in the historical experiences of his native Caribbean. Following his nationally acclaimed play “Kesnoh” and the novel, “Season of Mist”, both of which are based in real-life events of Saint Lucia, he weaves a story around a young school girl who was raped and murdered in the early 2000’s in the peaceful setting of a rural island community.

While, on the surface, it seems that Dixon is exploring a crime mystery, this work goes far deeper. The main theme of domestic violence which threads through the novel may surprise the non-Caribbean reader, whose images of Caribbean life are idyllic, even pastoral, and who sees these small societies as a playground in which to frolic and indulge their fantasies – and certainly not as a setting for crime and violence.

It is a superficiality that one understands, given that the Caribbean has, for decades, been represented in tourism brochures as the ideal get-away from the mundane, and certainly from the more jarring experiences of life. Hidden beneath this veneer of carefree sun, sand, sea and pulsating music however, is a history of colonial violence whose residual responses to oppression arguably continue to impact our Caribbean communities today.

Martinican Frantz Fanon, in his seminal “The Wretched of the Earth” argued that the revolutionary violence which erupted in various parts of Europe’s colonies from time to time, and which did not spare the Caribbean, was a natural and liberating response of oppressed peoples. The violence in which these societies were birthed and nurtured has also been reflected in the social relations in small societies in ways that are too often, at least until now, overlooked. One of the most virulent throwbacks of historical violence and systems of authoritarianism and domination is domestic violence. And there is nothing liberating or cathartic about it.

The gruesome murder and “envyòl” (Kwéyòl for rape) of the character Laurette, the allegation that her stepfather may have been the perpetrator, his arrest and remand in custody for nine years without trial, the mission of his detective son (and younger brother of Laurette) Andy, to prove that his father could not be, and indeed was not the bouwo (murderer) that many in the close-knit community of Bwa Nèf, Dennery made him out to be, is a story charged with emotion. The narrator, Andy himself, recounting the story in Saint Lucian/Caribbean nation-language and idiom, gives the story an authenticity that Dixon brings to his fiction. There is a distinct and poignant Saint Lucian-ness in his syntax, in his rendering of a Saint Lucian English interspersed with a Kwéyòl sensibilité which, far from being obfuscating, is lucidly expressive. He uses this linguistic technique boldly and successfully throughout the narrative. “You come from where you come from” (p. 128); “like a sikwiyé calling for his partner between a hand of ripe bananas” – some of the image-rich language that infuses Dixon’s story-telling in A Scream in the Shadows, and is just as masterful as his use of similar devices in Season of Mist, his poetry and drama. There are echoes of Walcott and perhaps of Kamau Brathwaite.

Lovence St. Mark was a smooth character, a suave dresser who had married Agnes when she was pregnant with a child not his. He had cared for the little Laurette as his own. As far as Andy could tell there was no difference in the way his father treated the siblings – Laurette, Marvin and himself. Andy was apparently unaware of Laurette’s different paternity until well into his teens. Could such a man have violated his own step-daughter?

Among the many subsidiary threads running through Dixon’s story are those pivoted on the inconclusive investigation of the case: the incompetence of the police, the under-resourced justice system, the internal politics of a police force whose officers are jockeying for promotion, the disposition that one does not interfere in “man and woman business” – which is pervasive within the police force as well as in the wider society.

Andy St. Mark, Lovence’s now grown, detective son hopes to cut through this maze and to arrive at the truth. The many unfollowed leads and unanswered questions are the basis on which Andy will explore the very real possibility that one or more of several other characters who might have had opportunity, perpetrated the crime.

The main protagonists, apart from Lovence and Andy, are to be noted. Agnes, Lovence’s wife and mother of Laurette, Andy and Marvin, is a loving and devoted woman who defends her husband and denies any brutality at his hand, to the very end – as is too often the case in such relationships of power, control and ostensible love. This is borne out powerfully when she says, “Lovence never put a hand on me from the day I know him. “He love me, he love Laurette, he love all his children” (p.129). Angel, Andy’s wife, is the gentle but firm, no-nonsense, make-her-own-money woman whom Andy relies on as a stabilizing factor as his world seems to fall apart. Sarge (Sergeant Willius) is the bridge between the police old guard and the younger officers – a man with an “open mind”. He mentors Andy and helps shore him up as he pursues his quest for truth. He gives Andy the hope that the justice system can be salvaged. And there’s Marvin, Andy’s younger brother, who will play a pivotal role in this narrative where the wheel of violence comes full circle.

Mac Donald Dixon does not claim to have the answers, he is not a social psychologist, but he underscores the need to actively search for solutions in small societies that are seemingly imploding with violence – domestic violence, as well as an escalating culture of brutality. Recent news headlines from across the Caribbean bear this out. The Saint Lucian dramatist and novelist has written a timely novel that will strike a chord with readers.

Congratulations to publisher Papillote Press, the small independent press based in both London and Dominica who continues to provide publication opportunities to contemporary Caribbean writers at home and abroad and to republish the works of major writers like Phyllis Shand Allfrey and Elma Napier.

A very insightful commentary by someone known to weave words as though he’s in love with the English language. After George Goddard has elucidated a point, whoever doesn’t get it wasn’t listening. In summarizing Dixon’s novel, he does such a good job, for a moment I thought he was giving away too much, but in the end it turned out to enough of an incentive to go out and get one’s copy.

Great job, you are doing authors a great service. Keep it up.