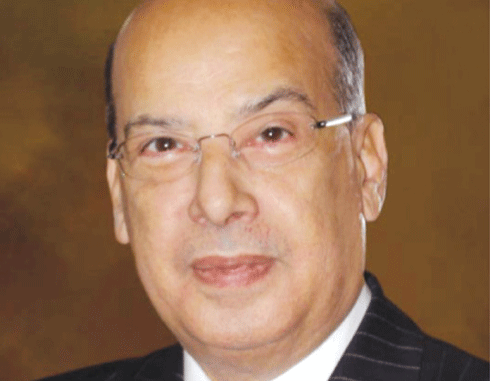

(The writer is Antigua and Barbuda’s Ambassador to the United States and the Organisation of American States. He is also a Senior Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies at the University of London and Massey College in the University of Toronto. The views expressed are his own)

REPORTS are wrong in stating that eight Caribbean Community (CARICOM) countries are on a ‘black list’ recently released by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) over Citizenship by Investment (CBI) and Resident by Investment (RBI) schemes that they operate.

The OECD has not ‘black listed’ these countries – at least not yet.

But the stage has been set for punitive action, unless there is a proactive and unified response by all these countries.

Essentially what the OECD said in its latest resistance to any form of tax competition is: CBI/RBI schemes can be misused to evade tax legitimately due to their countries of tax residence by the beneficiaries of these schemes.

In the statement, issued on 17 October, the OECD makes no distinction between CBI and RBI schemes, contrary to announcements from one Caribbean minister that suggests a differentiation. In other words, the eight CARICOM countries are all in this together, along with twelve other jurisdictions that have been named specifically.

The eight CARICOM countries (in alphabetic order) are: Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, St Kitts-Nevis, and St Lucia. They join only two member-states of the European Union (EU) – Malta and Cyprus – even though at least nine other EU countries operate a form of CBI/RBI schemes. Among the nine EU countries are Britain, Ireland, Italy and Portugal.

No explanation is given for the omission of these 9 EU states from the concerns over CBI/RBI programmes, and none is given for not including the EB-5 programme of the United States or the Quebec Immigrant Investor Programme in Canada.

These omissions apart, at least the EU admits that all of its member-states “have various incentives in place to attract foreign investment from non-EU nationals” and that “most of them have CBI or RBI schemes (so-called ‘golden passports’ and ‘golden visas’), characterised by the provision of access to residency in exchange for specified investments”.

All of that seemed to be well and good, until two of the smallest jurisdictions in the EU (Cyprus and Malta) and other small nations, such as the eight CARICOM states, joined in the schemes because of economic necessity.

Now, the EU and the OECD (in which the EU plays an influential role) have decided that CBI/RBI programmes pose risks for “corruption, money laundering and tax evasion”.

This bold claim is made even though the countries identified in the OECD October 17 statement have in place strong anti-money laundering regimes, Tax Information Exchange Agreements and Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties, and are implementing both the US Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) and the OECD’s Common Reporting Standards (CRS). FACTA and the CRS require jurisdictions to exchange automatically financial information of foreign persons and companies to other countries in which they are liable for tax.

The new OECD claim is that “identity cards and other documentation obtained through CBI/RBI schemes can potentially be misused abuse (sic) to misrepresent an individual’s jurisdiction(s) of tax residence and to endanger the proper operation of the CRS due diligence procedures”.

Of course, this claim can be settled easily by a requirement for all jurisdictions, everywhere in the world, to necessitate that account holders or controlling persons declare any residence rights they have in each jurisdiction in which they have it. In this way, submissions would be made to all the jurisdictions of residence of account holders and controlling persons, thus stopping any misrepresentation.

But, that is not the only new claim now being made by the OECD.

The Organisation also asserts that “high-risk” CBI/RBI programmes are those which “give a tax payer access to a low personal income tax rate of less than 10% on offshore financial assets and do not require significant physical presence of at least 90 days in the jurisdiction offering the CBI/RBI scheme”. This latter situation, which the OECD clearly wants terminated, would materially affect CBI/RBI programmes in CARICOM jurisdictions. It effectively dictates what tax rates should be and the conditions, which in their sovereign right, the CBI/RBI jurisdictions have set.

Given all this, if the CARICOM jurisdictions are to save their CBI/RBI programmes from decimation, they should form an alliance with the other 12 named jurisdictions to fashion a joint response before the OECD moves to its next step which, undoubtedly, will be a black list that calls for sanctions against them.

None of their interests will be served by any jurisdiction that chooses to enter an individual agreement with the OECD, setting a precedent which all the others will be obliged to follow.

Once any jurisdiction readily accepts the OECD dictates, unified action is disrupted, and all jurisdictions will be forced to acquiesce. This disruption of unified action has been the pattern of past responses to the OECD’s so-called ‘rules’. The consequence has been the steady destruction of the financial services sector and an attendant loss of revenues and jobs to the countries

The affected jurisdictions should take the OECD at its word that its concern is the misuse of CBI/RBI programmes by beneficiaries to hide their assets and escape reporting under the Common Reporting Standard. As explained earlier in this commentary, that issue could be easily satisfied, and CARICOM countries could collectively offer to do so.

What is more problematic because it invades the sovereign rights of states is the branding of CBI/RBI jurisdictions as “high risk” because they might have a low tax rate and no requirement for physical presence. Indeed, it is eminently arguable that these two claims do not obviate the obligations of the CRS and FACTA to report on the financial assets of account holders or controlling persons.

However, if these are conditions that the OECD implements, the CBI/RBI programmes in all but powerful countries will be decimated with disastrous effects on their economies.

That is why common cause to confer urgently with the OECD should be a priority of CARICOM countries. The decline of the economies of eight of them will impact the neighbourhood in which the other seven exist. All are involved, and all can be consumed.

Responses and previous commentaries: www.sirronaldsanders.com