THREE weeks ago, I and many other committed Caribbean integrationists declared that the unity displayed by CARICOM countries at the Organization of American States (OAS) on May 31 “was a moment for unbridled pride”. What happened on Monday, June 20, just days later, shattered that sense of pride as CARICOM countries not only reversed their unity but displayed their differences in public on a live Internet streaming watched worldwide.

The first occasion, as the second, was a ‘Meeting of Consultation of Ministers of Foreign Affairs’ of the 34-member OAS to discuss the situation in Venezuela. At the meeting on May 31, CARICOM countries presented a draft declaration, agreed by CARICOM leaders, which was an alternative to an existing draft backed by a Group of 14 countries (G14), led by the US, Canada, Mexico, and Peru.

The G14 draft, called ‘the Peru draft’, was interventionist in its tone and content and defied the Charter of the Organisation and its rules. Both St. Vincent and the Grenadines Prime Minister Dr. Ralph Gonsalves and Antigua and Barbuda’s Prime Minister Gaston Browne decried the interventionist and interfering overtones. They were right and Bruce Golding, the former Prime Minister of Jamaica was wrong in chiding them.

In trying to justify ‘interference’ in Venezuela, Mr. Golding drew a comparison to the Caribbean’s involvement in the fight against Apartheid in South Africa. I believe that, upon reflection, Mr. Golding, for whom I have a great deal of regard, would consider that comparison to be most inappropriate.

Because a few CARICOM countries had been encouraged to support the ‘Peru draft’ and the solidity of CARICOM was being threatened, CARICOM leaders convened a special meeting on May 29 to try to rebuild solidarity. In doing so, they produced a new draft declaration which they instructed should be used “in the negotiations for the final text which will be considered by the (resumed) OAS Ministerial Consultation Meeting”.

These instructions were contained in the CARICOM Secretariat Savingram No. 340/2017 of May 29 with which the draft of the leaders was conveyed to all Heads of Government and copied to all Foreign Ministers of CARICOM countries.

In other words, the draft declaration from the leaders was not – as it could not be – a declaration which would be imposed upon the other 24 members of the OAS. They themselves said it was a unified position to be used “in the negotiations for the final text” which all 34 governments of the OAS would consider.

The CARICOM leaders’ draft and the “Peru draft” were both considered at the May 31 meeting, but each failed to command the support of two-thirds of the membership (23 votes). The Meeting of Consultation then did precisely what CARICOM leaders wanted: they agreed the two texts would be used “in the negotiation for a final text”.

Ministers of all the OAS countries present at the May 31 meeting then asked their Ambassadors to negotiate a final text using the CARICOM leaders draft and the ‘Peru draft’ as the basis for their discussion. Contrary to what has been alleged, Ambassadors did not seek to arrogate to themselves any “authority to amend or rescind an authoritative decision of the (CARICOM) Heads”. Indeed, they were acting in compliance with instructions from Ministers who were themselves acting fully in concert with the decision of leaders as conveyed in the CARICOM Secretariat Savingram No. 340/2017.

In pursuance of those instructions, CARICOM Ambassadors to the OAS elected three of their number to negotiate with three of the representatives of the G14. On the CARICOM side were the Ambassadors of Guyana as current Chair of CARICOM, Riyad Insanally, the Ambassador of Barbados, Selwyn Hart, and me as the Ambassador of Antigua and Barbuda. For the G14, the negotiators were the Ambassadors of Peru and Brazil and the interim representative of the United States.

Two things are important to note: firstly, the CARICOM negotiators insisted on using only the CARICOM leaders’ draft for negotiation; we rejected the ‘Peru draft’ outright on the basis that it was too interventionist in its tone and content and, secondly, every CARICOM Ambassador was fully informed by red-lined texts of each stage of the negotiation with the request that they keep their governments abreast of the outcome of the negotiations which, at all times, was subject to approval by governments. The same process was followed by the G14.

To be fair to the G14, they demonstrated a great deal of flexibility despite opposition in their own camp to the acceptance of discarding the ‘Peru draft’. At the end of the negotiations, all but four paragraphs of the CARICOM leaders’ draft remained as written and of the four other paragraphs, very little of substance was altered except to identify matters to which the government and opposition in Venezuela had agreed as reflected in published communiques from mediators, including the Pope’s representative.

Until Prime Minister Gonsalves wrote and published his letter of June 16 to his colleague leaders, no CARICOM country had raised any objection to the negotiation or its outcomes. Indeed, several governments contributed language to the negotiators for the text.

When CARICOM Ministers convened on the morning of June 20, prior to the resumed meeting of the OAS Ministers of Consultation in the afternoon, it was assumed that all CARICOM countries were on board on the negotiated text, except for St. Vincent and the Grenadines. Several had indicated their support in writing or orally. At the CARICOM Ministers meeting, ably Chaired by the Barbados Foreign Minister, Maxine McClean, the Minister representing St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Camillo Gonsalves, made clear that his government was not supporting the negotiated text.

Ministers and other representatives were then asked by the Chair if any of them were of the same mind as St. Vincent and the Grenadines. Not one demurred. The CARICOM negotiators were then instructed to meet the negotiators for the G14 to settle the final text which we proceeded to do in good faith, having advised that St. Vincent was not part of the agreement in the exercise of its sovereign right.

Only after the negotiation was completed with little time before the start of the resumed Meeting of Consultation did Suriname indicate that it could not support one sentence in the agreed declaration. That sentence, which had been shared with all CARICOM representatives throughout the negotiation, called for “the reconsideration of the Constituent Assembly (in Venezuela) as presently conceived”. As it turned out that sentence, for whatever reason, became the basis for four other CARICOM countries to publicly and without notice, break ranks and declare their lack of support for the single negotiated document. CARICOM was split asunder, and the negotiations that had been conducted on behalf of all then seemed to have been conducted in bad faith.

The final text would have expressed the collective concern of all OAS states about the situation in Venezuela, call for an end to violence and for the government and opposition to return to dialogue, to address the need for food and medicines, for respect for human rights, the rule of law and democracy, including representative democracy, and declare the OAS ready to provide assistance to meet the serious challenges facing Venezuela.

The representative of St. Vincent then reintroduced the draft that CARICOM leaders had offered “for negotiation of a final text” as his government’s draft declaration. Therefore, CARICOM countries found themselves in the awkward and embarrassing position of having to vote on two drafts – one of which had been intended by CARICOM leaders for negotiation, and the other that had been negotiated with fidelity to the fundamental principles enunciated in the CARICOM leaders’ draft. The other OAS countries looked on aghast.

In the final vote of all the OAS countries present, the St. Vincent draft secured only 8 votes in favour while the negotiated draft garnered 20 yes votes. Again, neither draft secured the 23 votes necessary to be adopted and the meeting adjourned as it began with no declaration but with a severely wounded CARICOM and a paralysed OAS.

I abstained from both votes as did the representatives of Grenada and Trinidad and Tobago. As I explained at the meeting after the vote, I had negotiated in good faith for CARICOM with a CARICOM draft whose principles were steadfastly maintained. The final negotiated declaration was non-interventionist and had nothing that could reasonably be regarded as “interfering”. In good conscience, once the CARICOM centre collapsed, I could not vote for a declaration for whose achievement I had worked in the interest of a cohesive CARICOM stance. The pride I felt just 20 days before dissolved into profound disappointment and a gloomy mood.

CARICOM is the weaker for all this and it will not easily recover the soft power and respect that comes from 14 acting as one.

Responses and previous commentaries: www.sirronaldsanders.com

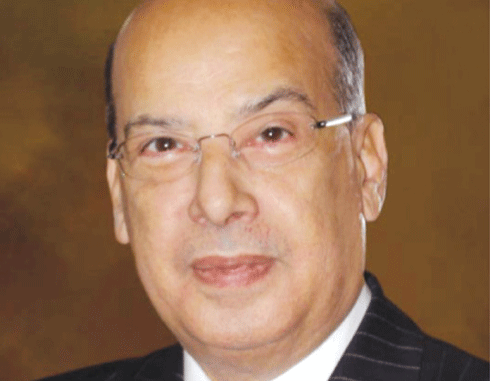

(The writer is Antigua and Barbuda’s Ambassador to the United States and the Organisation of American States. The views expressed are entirely his own).