Half my friends are dead.

I will make you new ones, said earth.

No, give me them back as they were, instead,

with faults and all, I cried.

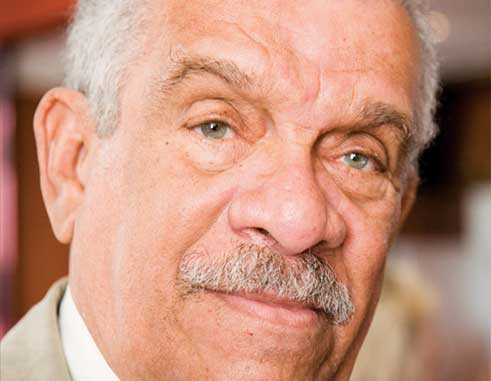

Those are the opening lines of Derek’s poem “Sea Canes,” a poignant tribute to the blessing of friendship, which he extolled in his poetry as one of the bounties of life. So now he has gone to see his friends again, “as they were, […] with faults and all.” Now, in his memory, we recite the names of some of them, friends, and family who were friends: Alix (Teacher Alix, his mother), whose “house sang softly of balance, / of the rightness of placed things”; his twin brother Roddy, buried in Choc cemetery, “in the short street / where my brother and our mother live now / at the one address […]”; so too his sister Pam. Then there was his revered mentor, Harry Simmons, “the fervor and intelligence / of a whole country”, and Derek’s early painting partner, Gregorias/Apilo/Sir Dunstan St Omer, with whom he “swore” “that [they] would never leave the island / until [they] had put down in paint, in words,” every distinctive, unrecorded detail of its landscape.

Next come the departed friends who worked under his direction in his history-making Trinidad Theatre Workshop, themselves enshrined in memory:

Wilbert Holder, Claude Reid, Ermine Wright, Laurence Goldstraw, Errol Jones and Stanley Marshall. Also, of stalwart support in the running of the Workshop in its crucial years, his second wife, Margaret, herself a good friend.

Then his writer-friends: the Jamaican novelist John Hearne and poet-educator John Figueroa, the American playwrights Arthur Miller and August Wilson, poet Robert Lowell, and most of all his fellow Nobel Laureates, the Irishman Seamus Heaney and the Russian Joseph Brodsky, his “sparring partners”.

To recite these names, and others I haven’t called, is to trace the exceptional path of Derek’s achievement as poet and playwright, an achievement all the more momentous because it began at a time when, as he said in one of his early, self-published poems, Epitaph for the Young, “There [was] no West Indian literature.” That was in 1949. He was then in the process of becoming one of the prime makers, not only of Caribbean but of world poetry, and, in the process, a maker of Caribbean drama as well. At age ten, he was made by his teacher and the Headmaster to read to the school a poem he had written. From then he began to attract attention, working single-mindedly at his gift, increasingly prolific, always working to perfect his craft. Remarkable, too, is the fact that his poetry hit trans-Atlantic, metropolitan, literary headlines well before he went to live outside the Caribbean.

It was only a few months ago that his latest book of poems was published, nearly twenty-five years after he had won the Nobel Prize. It was a new departure, his poems written to interface with paintings by Peter Doig, the highly regarded Scottish painter who had made Trinidad his home since 2002. At the launch here in Castries, just three months ago, on December17, both painter and poet were present. At the end of the function, Derek had to be rushed to hospital.

We celebrate now the maker, who spoke, as Caribbean person, in words and in paint, who spoke for the Caribbean, to and with itself and the world. He helped us articulate our engagement with history, with the colonial legacy of the Caribbean. He does this memorably, etching emotions and ideas through his eye-opening representation of our landscape, through images, metaphors and rhythms that fix themselves in our memory, through his always unobtrusively inventive respect for form, through the subtlety of his rhyming. As he said of himself and his friend St Omer, “We were blest with a virginal, unpainted world / with Adam’s task of giving things their names […]”

Caribbean history and the colonial legacy are also engaged, in varying ways by some of Derek’s plays, such as the always-appealing Dream on Monkey Mountain, Ti-Jean and His Brothers, Remembrance, Pantomime, and A Branch of the Blue Nile. In respect of his work in theatre, as playwright, producer and director, he is one of the chief begetters of West Indian drama. He laid historical ground in his role as co-founder of the St Lucia Arts Guild, and, more comprehensively change-making, as founder of the Trinidad Theatre Workshop, a few of whose legendary members are with us today. In plays like Dream, Ti-Jean and The Sea at Dauphin, he gave voice to the people and drew on the creative power of the folkways. Who can forget the sea-faring Afa of Dauphin, Makak of Monkey Mountain, and the spiritedly commonsensical Ti-Jean, all of whom challenged history and the circumstances that had worked against their affirming, in Ti-Jean’s phrase, “what it is to be a man”?

When, as circumstances would have it, Derek left Trinidad for the United States, he carried with him, with results for the record books, his genius for mentoring creativity, not only in writing, but also in stagecraft. In so doing, he advanced the Caribbean presence, in poetry and theatre, in the wider world. At the beginning of the 1980s, he was appointed to the faculty of Boston University, where he taught creative writing for more than twenty-five years, and, even more history-makingly, founded the Boston Playwrights’ Theatre, which still flourishes. The regard in which he is held there was enacted in an event, in October 2015, in which former students, colleagues and friends paid tribute to him, in readings and songs from his works, and in recollections and anecdotes. He was not well enough to attend, but the occasion was alive with his presence.

The Nobel Prize was no doubt the highest of the many honours and awards that he accumulated over the span of his career, including the Order of the British Empire, Honorary Membership of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a MacArthur “Genius” Award, and the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry. Nor has the prophet been without honour in his own country, his own region; for example: Trinidad’s Gold Hummingbird Medal, and a Gold Musgrave Medal of the Institute of Jamaica. And there have been Caribbean firsts. In 1973 he became the first graduate of the University of the West Indies to be awarded an honorary doctorate by the institution. In 1991, the year before the Nobel, he was one of the first three recipients of the CARICOM Medal. Then, crowningly, in Nobel Laureate Week 2016, he was made one of the first Knights Commander of the St Lucia that had made him.

We mourn and we celebrate a genius who was a prodigy, a maker, a Caribbean man who has made us and the world see more clearly Caribbean landscape, Caribbean light. But we also mourn and celebrate a person, someone with the virtues and the shortcomings that defined him as the person whom those who knew him valued. I remember him as unassuming, never one to blow his own trumpet, not one given to “talking shop,” but famous, if not notorious for his “corny” jokes. When I read his poem “The Muse of History at Rampanalgas,” I asked him if he knew the origin of the name Rampanalgas, a remote place on the north-eastern coast of Trinidad. He said that he didn’t, but then quipped that perhaps a guy named Rampanal once had a gas station there.

He was a generous man, considerate of others, always willing to acknowledge and promote talent where he detected it. He was a kind, loving, responsible father and, in his daughter Anna’s words, “a doting, absolutely besotted grandfather.”

At the same time, he could be surprisingly curt and dismissive on occasion; ironically, for instance, when some stranger, often female, who greatly admired his work, went up to speak to him, to pay homage, after a reading by him. In theatre workshop sessions, and in rehearsals, he could be a hard, even infuriating taskmaster, as he pulled the rug of complacency from under the actors’ feet. In his earlier days especially, he could lose his temper and explode. One day in the early 1970s, I ran into him in the departure lounge of Grantley Adams airport in Barbados. Noticing that his right hand was bandaged, I asked about it. He replied, with a telling smile, that he had pushed his hand through a door. I was to get the true story some time later, from a mutual friend, who told me that Derek had got angry at a house party in Port of Spain one night, and had punched a door so hard that his fist went through it. In other words, “pushed” was a euphemism for “punched.”

We celebrate now the life of someone who was a model of commitment to the craft of verse and the making of theatre as a career, a model all the more admirable in West Indian society, where, traditionally, even the few who might have had the urge to do likewise were brought up to think that writing poetry could at best be only an avocation.

Let us set, like a halo, around him, his luminous poem “The Season of Phantasmal Peace:”

Then all the nations of birds lifted together

the huge net of the shadows of this earth

in multitudinous dialects, twittering tongues,

stitching and crossing it […] until

there was no longer dusk, or season, decline, or weather,

only this passage of phantasmal light

that not the narrowest shadow dared to sever.

[…] [I]t was the light

that you will see at evening on the side of a hill

in yellow October, […]

[…] it was their seasonal passing, Love,

madeseasonless, or, from the high privilege of their birth,

something brighter than pity for the wingless ones

below them who shared dark holes in window and in houses,

and higher they lifted the net with soundless voices

above all change, betrayals of falling suns,

and this season lasted one moment, like the pause

between dusk and darkness, between fury and peace,

but, for such as our earth is now, it lasted long.

On behalf of the Governor-General of St Lucia, Dame PearletteLouisy and the Prime Minister of St Lucia, Mr Allen Chastanet, and the Government of St Lucia; on behalf of his loved ones: Sigrid, his bright-spirited, unswervingly supportive partner of some thirty years; his son Peter; Lizzie and Anna, his “two dear daughters” (to use a phrase from one of his poems), his grandchildren and his nephew Nigel; on behalf of his other relatives, his friends and admirers; on behalf St Mary’s College; on behalf of the people of St Lucia, on behalf of the West Indies and the World, we say to the boy from Chaussée Road: Derek, Sir Derek Alton Walcott, may this evanescent but transcendent light shine on you, and may you rest in the radiant moment that is the season of phantasmal peace.

Edward Baugh

March 22, 2017

March 25, 2017

![Simón Bolívar - Liberator of the Americas [Photo credit: Venezuelan Embassy]](https://thevoiceslu.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Simon-Bolivar-feat-2-380x250.jpg)