A review of the Cultural Development Foundation’s Poetry Live.

SO many persons dream of going home. Home, however it is defined. But getting to a place, involves some form of travelling. Be it physical, mental, spiritual.

SO many persons dream of going home. Home, however it is defined. But getting to a place, involves some form of travelling. Be it physical, mental, spiritual.

Through its Master of Ceremonies, at the Poetry Live event of the 25th March 2015 Artreach event, the Cultural Development Foundation announced to its audience (both those in house at the NTN studio and the wider audience viewing the event live via NTN), that it would be taking them on ‘a journey through metaphor and rhythm’.

What a journey it turned out to be.

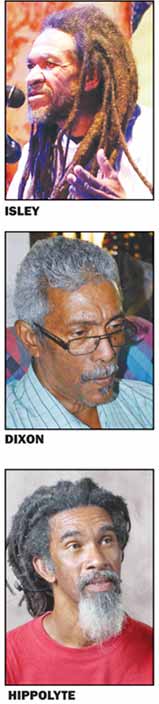

Through the rallying rhythm of his drum, which found an audience willing to respond to its call to travel with it, Rapso Poet RasIsley lamented that he had nothing to do, nowhere to go; he complained that when he thought that someone had journeyed to ‘foreign’, it was only later to discover that the person had only journeyed inland to a correctional institution; and that when he went on the block, it was only to be with people who seemed to be going nowhere. With the audience clapping and singing along, all seemed to be certainly on a journey of sorts. Perhaps there were those who identified with the lamentation; or perhaps, it was also their story. Perhaps, there were those who were encouraging Isley to sing out so that, that of which he spoke, would not become the legacy of their children.

The featured poet that night was Rhodes Scholar and Jamaica’s Poet Laureate, Mervyn Morris. Through the recitation of his poetry, he carried the audience with him to familiar and non-familiar places of love, cultures, childhood, climates, the Garden of Eden where Eve met up or ‘buck up’ with a serpent talking; Morris took the audience even to that green hill far away where Jesus is nailed to the cross; the rasta-ish brother, nailed to the neighbouring cross, begs of the Man himself that “When your Kingdom come, remember I”.

Morris’ poems, too, found an audience willing to respond to the journey. His poem with the catchy call of “Hey ho the sun and the rain”, employed the audience in the call and response voyage so often rejoiced in our songs, from hymns to calypso. Another place to which Morris took the audience was to that space which is given so many names and yet still remains very much a mystery: Death.

“When my father died, my mother cried” recited Morris; but he could not cry and so he allowed his mother to take him where she could also cry on his behalf; her tears were his.

This is a reverent place: where one person weeps for another. That is a place which, from the words and dispatches of the poems that were read that night, is either lost or in imminent danger of being lost. To echo RasIsley’s foreboding words, it is a place of nowhere.

In the readings of six selected poems from the book ‘Sent Lisi’, Poets Esther Matthew and Adrian Augier provided the travelogue of insights of Poets who too spoke of places to go and sadly, places no longer available as destinations.

In one such selected poem, TeteChemin, Poet Travis Weekes writes: ‘Victor…missed school on banana days/having realized that banana boxes/are the “New Capital Arithmatic”…TeteChemin…lettered with children whose dreams drip with tears…’

In another selected poem, I cannot find this island, Poet Jane King-Hippolyte writes: ‘I cannot find this island lovely in drought…right now it is a waste land creaking in drought…our sins have found us out…I wish I was a priestess…dancing, howling round a churning fire that would never go out…make a path through doubt/ bawling incantations…to see this island once again emerald…’

But, is all hope lost? In the featured poem, Kwéyòl Canticles, John Robert Lee writes that there is still hope; So ‘Let us praise His name with an opening lakonmèt,/and in the graceful procession of weedova;/let laughing, madras-crowned girls rejoice before Him in the scottish/and flirtatious moolala…turning in quick-heeled polkas…for when the couples end the gwan won,/you alone must dance for Him your Koutoumba…He is the Crown…the Dancer of creation…hand of the incarnating Word.’

Perhaps, suggests Poet KendelHippolyte, in another featured poem, Lines on a sidewalk, ‘Where the sidewalk splits…now fractured/there a fault line of possibility where new breaks into knowing/and you sense your eyes warm wider open from, and to, a light/inciting you to, for the first time, yet again, see./See: that no matter how, how much, how often, how long we slab the earth,/she will breach us, grab back her ground from our suave hands…See: that underneath our feet she is convulsing…she will finally become what is hidden from us…we might eventually reach a destination… the sidewalk should remain cracked, for…unnoticed light that –briefly, imperfectly – relumes/another way.’

Could that new destination be a place which we have always known but perhaps forgotten? Or a new Country altogether? Can we, in the words of Jane, ‘make a path through doubt?’

Is there a place to which we should go, where we have gone to before and immersed ourselves in the pleasures of the land, where we wept for each other? Yes, says Poet McDonald Dixon, in the selected poem We will go to that place in the country:

‘We will go to that place in the country,/away from asphalt eyes that bleed lost lives…there’s a river…a waterfall…sighing casuarinas resound…roast corn on a grate…logwood blossoms…the sun puts on its Sunday face…’

But, warns McDonald, ‘we must go to that place in the country -/ before December curdles the stagnant air.’

Before our hearts grow too cold.

But, is that a place to which our children wish to go?

The final featured poem, Perhaps the Children, came from Poet Adrian Augier, who pondered thus ‘…perhaps the children/ don’t need our poetry,/as citizens of one great world/don’t need the baggage of identity./no need to…speak out;/no urgency to wake…’

Is this the place where RasIsley will find his children moving towards? That this is some place to which we will all arrive?

Perhaps, yes it is so, Augier might answer. For his poem continues that: ‘without the wonderment of words,/the careful turning of a phrase,/the subtlety of tone and texture/that once raised our letters, songs and sermons/beyond the one-dimensional…’ then, on this soil, there may very well come a time of a ‘drought of poets’.

With the audience seemingly wandering in their private answers to Augier’s and the other Poets’ ponderings, the question and answer session, that would end the evening, began.

“So”, asked John Robert Lee of Mervyn Morris, “we have come from a golden age of Louise Bennett and Derek Walcott, where are we now? Where is poetry going?”

Morris answered, quite simply: ‘Poetry is going wherever the talent is going.”

So, it seems, maybe we do have something to do and somewhere to go to after all.

By Floreta Nicholas

![Simón Bolívar - Liberator of the Americas [Photo credit: Venezuelan Embassy]](https://thevoiceslu.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Simon-Bolivar-feat-2-380x250.jpg)