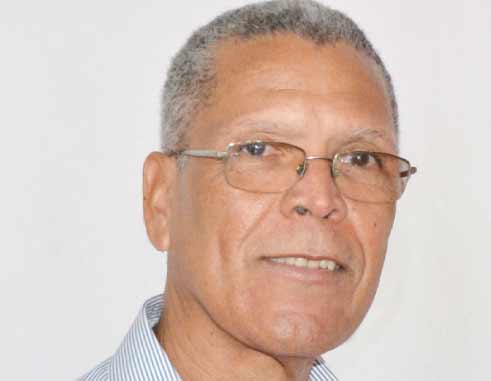

DURING that interview given by Prime Minister Chastanet at the training session in governance for public officials in January of this year, (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_AoCyw1v-GY), our Prime Minister made two more statements with regard to the governance of our country that bear examination.

In the first, he indicated that his government intended to promote the development of a professional civil service and we applaud all efforts made in this regard.

In the second statement, he suggested that “the role of the public is to vote for a political party or support a particular manifesto which will then guide the country moving forward”. He continued with “Our role is to make sure that we’re staying within that framework; the job of the professionals is to give us the best way to achieve those things”.

Granted that in that interview the Prime Minister was focused on development of good governance practices by his Cabinet, and by the Civil Service, but in making this statement he omitted to mention the most significant element of a guarantee of good governance – us. Our role is apparently limited to that of casting a vote at election time while the watchdog role of ensuring that Government sticks to its manifesto is assigned to his own Cabinet.

We have previously differed with our Prime Minister’s approach to transparency in that interview, (Part 1), and trust that, given the circumstances of the interview, it reflects a focus on the performance of the Civil Service rather than an unconscious neglect of us. Whatever the case, the effect is the same, as the information vacuum remains unfilled.

This vacuum applies even to ordinary matters, with only recently a leading accountant being moved to suggest that the methodology for calculation of the price of gasolene should be published by Government so that the constant bickering over its adjustment could be brought to an end.

Yet, there is cause for some hope, because three months after that above-referenced interview, our Prime Minister is reported as confirming his government’s “pride in being a government of accountability, transparency…” when discussing the then forthcoming budget. He indicated as well that “we are instead proposing a four-year strategic development plan for this country…”, and continued with “the details…was (sic) discussed with social and economic partners in the run up to the budget”. (stluciaonline, April 25).

In making that announcement, Prime Minister Chastanet recognized the need for consultation, but did not consider the need to extend that to the general public. One result is that while the Estimates of Expenditure were debated in Parliament at the end of April, they remained hidden from public view until publication on the Ministry of Finance’s website on June 28, a week after the end of the protracted debate.

This delayed publication of the Estimates of Expenditure is not unusual and also happened last year with the SLP government, as the public is routinely excluded from the debate. But in Barbados, a cursory check revealed that the draft estimates were laid in their House of Assembly on March 7, published on the Parliament website the same day, and debated over the following week.

For a clear presentation of a country’s budget estimates, that of the government of St. Kitts and Nevis for 2016, (which we used as a benchmark in last year’s budget discussions), is instructive (mof.gov.kn/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/2016-Budget_Estimates-Volume1.pdf). Not only is the document readily understandable, but the Minister of Finance’s introductory message indicates that “The Format adopted for the presentation of the Estimates is intended to create greater transparency and accountability to the citizens of the Federation”, clear recognition by that government of the importance of its citizens in the budgetary process.

The non-availability of information from our government does not stop there as, in the UK, a rolling digital edition of the Hansard record of Parliamentary proceedings is available throughout a sitting, and confirmed the next day (hansard.parliament.uk/about). In St. Lucia, while Hansard is produced digitally, only a hard copy is eventually published, and reading it requires a visit to the Parliament Office.

The same applies to laws, published digitally and freely available in the UK, (legislation.gov.uk), but which the public here has to pay for. We can accept some delay, but what is there to stop Hansard from being published on a government website, or from making our laws freely available digitally? We’ve already paid for preparation of the digital text and every government department maintains a website.

This information vacuum can only exist because we do not matter to our governments, apart from that brief period leading up to and including elections day. This approach to governance not only destroys public trust and confidence in government but also fuels the antagonistic relationship between supporters of the two parties. There are obviously politicians who thrive in this environment but the country pays a steep price in the poor quality of decision-making which results.

Next week, we look again at St. Jude Hospital and the disinformation which has emerged to fill the information vacuum.