Introduction

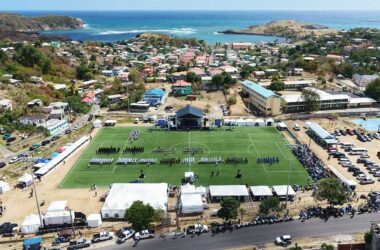

COVID-19 has required governments to turn to digital interventions – and become more data-driven – to enhance the efficiency, resilience, and inclusivity of public services. Small Island Developing States (SIDS), in particular, are embracing new technologies. In the midst of the pandemic, Cabo Verde, São Tomé and Principe implemented open-source district health information systems to enhance health coverage, whilst Dominica launched a digital marketplace for freelancers to generate income online.

This growing digitalisation means that public services are becoming ‘always on’, reaching wider and more diverse groups of citizens, and generating unprecedented amounts of data. This ‘revolution in data’ provides exciting and new opportunities to improve the relevance and impact of public services – and to ensure that no one is excluded. However, using this data to drive better public services – and to understand what does and does not work – requires new tools, and new ways of thinking and working. It requires ‘digital analytics’.

Managing our ‘digital crumbs’

Digital analytics begin with the ‘digital crumbs’ of our online lives. As we interact with digital systems and services, data is generated – both from our digital actions, but also behind-the-scenes. Active data collection (for example, online surveys or chatbots) requires people to input information, whilst passive data (such as how we browse a website) is often an ‘invisible’ by-product of our digital activity – and requires little action or involvement.

With new, and more expansive, digital products and services, this data is only increasing. From the sensors in our phones, to data provided by images, audio, videos, and applications. This is starting to translate into real-world impact. From analysing mobile crowdsourced data to improve urban waste management, to the Maldives’ deployment of drones for disaster risk assessment. These new technologies are making data collection more accessible. The data that is now able to be collected is also unprecedented – it is much more granular, more personalised, and often analysed in real-time.

Putting digital analytics into practice

Digital data and analytics present real opportunities for island governments to ensure that public services meet the needs of their citizens. In order to achieve this, governments will need to tackle the following priorities:

1. Focus on the citizen

Go where they are, use the channels that they’re on, and add value in all digital – and broader – interactions. It’s crucial that digital public services are not extractive, and instead provide value to citizens – even when collecting data. Measurement should also be shaped by how citizens and other stakeholders perceive ‘success’, while respecting the human dimension of digital and data. It should not detract from the user experience. The most useful, inclusive, and appropriate data collection methods are those that align with users – and their context. These efforts must be inclusive. Data collected through digital channels – by design – could exclude those who are ‘offline’, lack digital skills, confidence, or trust, or underrepresent those who are marginalised (who are mainly women): the poor, less educated and digitally savvy, and those with less time.

2. Focus on data quality

No amount of analysis will make up for collecting incomplete, biased, or inaccurate data. So, use tools and channels where you can be sure that you will collect the best data. This could mean using less high-tech, or even offline, methods of data collection. This is particularly important if looking to use data to drive broader innovation. Maximising the benefits of open data (or public intent data) requires granularity, good coverage of the population of interest, and comparability. Gathering more types and sources of data is not always the answer.

3. Test, learn, and iterate

Build goals and measurement priorities into programme design. Approaches like Lean Data can be valuable. Most importantly, be driven by these research and policy questions – and not by technology or other tools. This can often be an iterative process, informed by learning from citizen research and feedback – and could include identifying ‘positive deviants’ as benchmarks or models for improvement. Iteration can be particularly important when working with digital platforms – where data can quickly become ‘historic’ and ‘drift’ with changes in user behaviour, digital systems, and population over time. This can pose real challenges to the accuracy and relevance of initial data collected and analysed.

4. The tech is the (comparatively) easy bit

These new types of data require new skills, processes, and workflows. This may demand organisational change to ensure that digital analytics can generate useful insights and inform policymaking. These changes may also extend to shaping effective collaborations with the private sector – often custodians of digital data. For SIDS, in particular, reaching the ambitions of the SAMOA Pathway and the 2030 Agenda will require considerable investment in building capacity for data capture and analysis, both for attaining the goals – and measuring progress and gaps in delivering on these priorities.

5. Ethical principles are paramount

The power and potential of digital analytics demands that we prioritise the rights and privacy of individuals. This means differentiating between what we ‘can’ do versus what we ‘should’ be doing when collecting or using data – and putting dignity at the core of our thinking. Clear processes and policies should be in place for data handling throughout the ‘data lifecycle’ – from project planning to data collection and analysis, as well as reuse and disposal. This is not just about avoiding harm – it is about ensuring that citizens benefit from the use of their data, and gain value from these activities and interactions.

The way forward

Digitalisation has been accelerated by COVID-19 – and is now an essential component in driving SIDS’ recovery from this protracted pandemic. It also offers the potential to go beyond SIDS’ pre-pandemic green and blue transition trajectories. However, locking in these gains and ensuring that we leave no one behind requires rethinking our understanding of ‘success’ in the digital age – and the tools and techniques that we use to measure digital interventions. Each data point can represent a person’s needs, realities, and aspirations – and provides an opportunity to transform their lives and livelihoods.

However, digital analytics is one tool in our measurement toolkit. The digital divide is very real, and we must not entrench inequality by using insights from part of the population. Similarly, we should not forget the rigour learned through offline methods: we still need to focus on understanding citizens (including bias and gaps in data) – and translate insights into decision-making. This highlights the importance of building strong foundations and enabling environments – including learning from other governments and private sector partners that are at various stages of their digital transformation journeys. Digitalisation is a collaborative process – and one that no one country has completely figured out.