THE recent furor in Grenada over whether slave history has a role in the island’s tourism promotion and this month’s Bicentennial Anniversary of the British Slave Trade Act (which limited the number of slaves that slave ships could transport) are important developments that fit smack in the middle of the ongoing discussion on CARICOM’s quest for Reparations from Europe for Slavery and Native Genocide.

Today, just over 180 years after Abolition in Britain, descendants of African Slaves in the Caribbean and The Americas are demanding Reparations for Slavery from Europe and America.

In the Caribbean, the demands include an apology and atonement for 400 years of both Slavery and Native Genocide; in the USA, it’s about compensation for African American descendants of slaves; and in South America, today’s descendants of Africans (who arrived both as shipwrecked mariners and slaves) are demanding their fair share of recognition, equality and atonement.

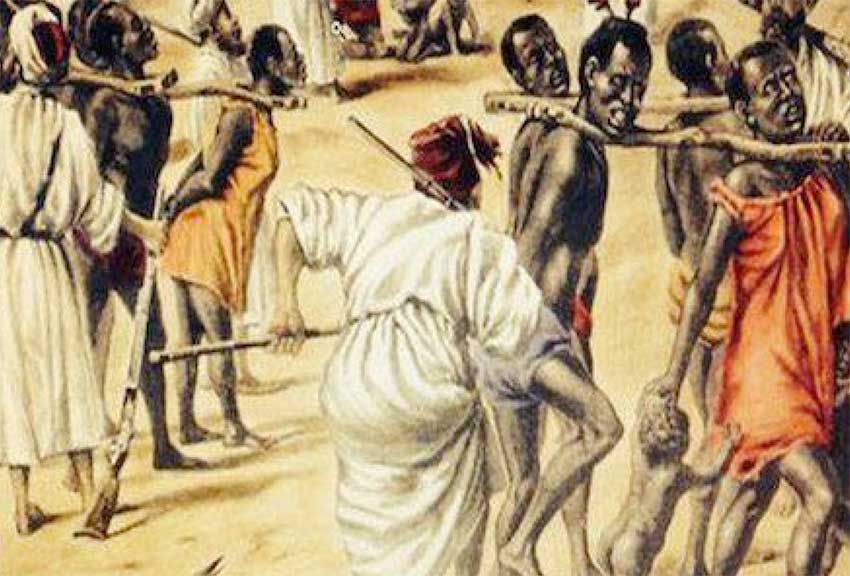

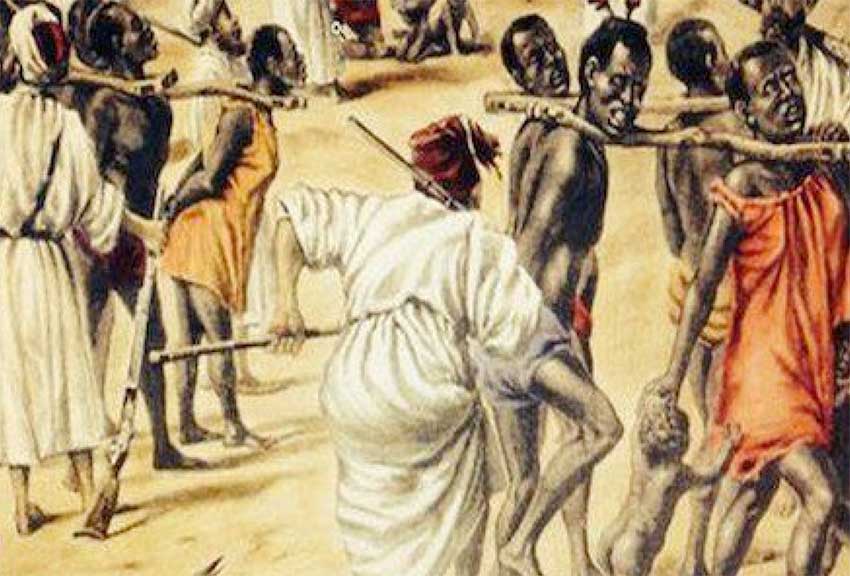

Africa and the Caribbean experienced the brunt of the brutal slave trade that saw Europeans sail to West Africa, kidnap millions of men and women and ship them like animal cargo to the newly-colonized ‘West Indies’ captured through wars of extermination against the original native ‘Caribs’ and ‘Arawaks’.

While the focus of British and French slavery was mainly concentrated on the Antillean (Caribbean) islands and mainland territories that they claimed to own (including Barbados and Haiti), the Portuguese and Spanish concentrated on South American mainland territories such as Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Chile, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela, as well as the larger islands of Cuba and Puerto Rico.

In the case of The Americas (except in Brazil), African descendants form small minorities — unlike the 15 Caribbean Community (CARICOM) member states, where they form an absolute majority in each case.

CARICOM governments have thus easily and collectively agreed to a joint approach to the European Union (EU) member states that benefited from Slavery, inviting them to discuss reparations by way of acknowledgement and atonement.

The EU countries are not known to have responded to the CARICOM request for discussions. Former British PM David Cameron (while still in office) said during an official visit to Jamaica in late 2015 that the CARICOM nations should forget about Slavery and Reparations and move on. He also posited that traditional aid and assistance given to former colonies by Britain (and other European states, by extension) since independence to the former colonies, has sufficed.

Britain, Denmark, France, The Netherlands, Portugal and Spain may have problems acknowledging their respective and collective roles in the Slave Trade. But that would be very much unlike two centuries ago, when France demanded reparations after the first African slaves in the Caribbean – and the world — successfully revolted.

Haitian slaves, led by Toussaint L’Ouverture, rebelled in 1791 and declared their independence in 1804. Not even in Africa had a free nation yet been born and the humiliated slave masters enlisted the support of the French government to make the former slaves pay dearly for their freedom.

In 1825, France demanded 90 million Gold Francs to recognize Haiti’s independence — the same amount demanded in compensation by the former slave masters.

Historians and economists agree that this high cost paid by Haiti to France over 122 years (payments continued until 1947) is largely responsible for the country having been almost eternally anchored in poverty.

In 2003, Haitian President Jean Bertrand Aristide called on Paris to return the 90 million Gold Francs, by then estimated at US$21 billion. Soon after, however, he was swiftly and secretly taken hostage by US and French forces and exiled to South Africa.

French President Francois Hollande, in May 2015, ahead of a visit to Port au Prince, said Paris “will repay its debt” to Haiti – only to later retract, saying he only meant repaying France’s “moral debt”.

The Hollande disappointment notwithstanding, no other concerned EU member state has even mentioned the possibility of considering paying reparations for slavery – in the Caribbean or North or South America.

Same in the USA where not even President Barack Obama accommodated calls to initiate Reparations moves and to pay to survivors the wages of the slaves who built the White House.

In 1865, Union General William Sherman set aside thousands of acres of land for newly-freed American slaves by way of a special field order. But President Andrew Johnson soon returned the titles to the original white owners. Freed slaves were also each promised “40 acres and mule” to start their own lives. But here too, the vast majority was disappointed.

The US Congressional Black Caucus has for the past 28 years backed a bill called HR-40, submitted annually by Michigan Rep. John Conyers, calling for a commission to study “the Reparations Proposals for African Americans Act”. Designed to examine the negative effects of slavery, it also seeks to “recommend appropriate remedies”.

But HR-40 has long been referred to the House Judiciary Committee, where it has since been gathering dust…

US Blacks are somewhat divided over what mechanism to use to assess the real costs and value of slave wages and related rates of conversion over the centuries slavery lasted.

Likewise, White Americans largely reject the Black calls for Reparations, some seriously arguing that ‘Slaves were freed by the Civil War’ and ‘Blacks (and Latinos) have benefited from Affirmative Action’ US government policies over decades.

The reparations movement is, however, gaining traction across the hemispheric horizon.

The momentum has got going in South America, an International Reparations Conference held in Cali, Colombia in March 2017, essentially to outline a road map for the movement for recognition and inclusion of the African-descended minority across the continent.

The African Americans are encouraged by a 2016 report by the Geneva-based United Nations Working Group on People of African Descent, urging US lawmakers to implement reparations, citing “a legacy of colonial history, enslavement, racial subordination and segregation, racial terrorism and racial inequality.”

Also, according to an exclusive poll released in March 2017 in conjunction with a new PBS Series ‘Point Taken’, 40% of US ‘millennials’ think there should be reparations for African American descendants of enslaved people.

Indeed, some of the leaders of the revived reparations movement in the USA are confident enough of the momentum gained thus far to conclude that ‘This could be Reparations’ best chance since 1865.’

In the Caribbean, the governments’ approach is naturally quite different from The Americas — more diplomatic than demanding, emphasizing dialogue over confrontation.

In March 2014, the CARICOM governments unanimously adopted the 10-point plan to demand “Reparatory Justice for the victims of ‘Crimes Against Humanity’ in the forms of Genocide, Slavery, Slave Trading and Racial Apartheid.”

A CARICOM Regional Reparations Commission (CRC) was also appointed (chaired by the Vice- Chancellor of the University of the West Indies, Professor Sir Hilary Beckles), with National Reparations Committees also established in member states.

The Caribbean hasn’t put a price tag on Slavery, even though a sum of US$17 trillion is often mentioned. Instead, it’s seeking a mutually-agreed CARICOM-EU approach to what forms the atonement will take to the common and mutual benefit of all the CARICOM states and peoples.

Failing this negotiated approach, however, the Caribbean countries reserve the right to file formal criminal charges against the culprit EU member states at the International Criminal Court (ICC)).

Citing the will of the Western world to proudly acknowledge and atone for the Jewish Holocaust, reparations paid by the US government to Japanese interned during World War II and to US Native Peoples, as well as Britain recently being ordered (by its own courts) to pay reparations to tribal Kenyan ‘Mau Mau’ independence fighters, CARICOM feels it has a very good case.

Those demanding Reparations for Slavery everywhere are also buoyed by the UN’s declaration of 2015 to 2024 as the Decade for People of African Descent.

The CARICOM Prime Ministerial Subcommittee on Reparations (led by Barbados Prime Minister Freundel Stuart) met in late April 2017 to update itself on developments to date.

In the meantime, the 15 member states, including Haiti, are preparing their individual legal cases for collective submission to the ICC should the concerned EU member states continue to dodge and dither to duck their individual and collective responsibilities for the greatest ‘Crime Against Humanity’ known to mankind.

The Reparations demands by African descendants in CARICOM and The Americas have the backing of regional and international entities, including similar non-governmental Europe-based movements and an increasing level of interest and support from African states and entities, including the African Union (AU) and the Pan African Congress (PAC).

The European and American governments today may decide to duck their responsibilities. But the current strong Reparations demands on them, whether achieved today or tomorrow, also offer added hope to the likes of the Australian Aborigines and New Zealand’s Maori first peoples, who may have received formal apologies, but continue to feel treated less than equal in the lands they first inhabited.

Meanwhile, the Grenada ‘Slavery and Tourism’ discussion is an interesting starting point to revive earlier discussions on the establishment of a National Reparations Committee (NRC) for Grenada, Carriacou and Petit Martinique, one of the only three CARICOM member states (others being Belize and Saint Kitts and Nevis) still without one.

A Grenada NRC will not only be in line with the reality of the vast majority of CARICOM member states, but will also facilitate ongoing discussion across the three-island state on Reparations and related issues, during the UN Decade, which continues until December 31, 2024.