Battling Against ‘Vagabonds of Culture’ and ‘Squanderers of Tradition’

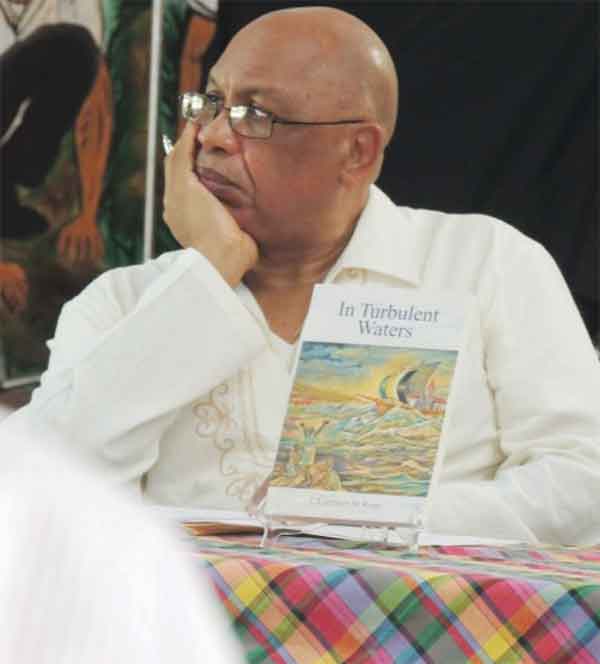

FR. Lambert St. Rose is one of St. Lucia’s best-known Catholic clerics. Whenever he’s speaking from the pulpit or using his literary skills to give voice to his thoughts and feelings, he never fails to command attention. Esteemed and admired by many, he has also been a source of unease and even trepidation to some, both in and out of the Church.

In this era of crass materialism, when pastors often resort to feel-good sermons about how faith in Christ can make you rich and boost your economic status, doing so in a way that appeals to the emotions but do little to challenge souls to seek renewal and conversion, Lambert St. Rose’s contempt for appeasement and his refusal to kowtow to political correctness have long made him an outlier and somewhat of an enigma.

Inspired by the cruel realities of the post-colonial Caribbean, he’s more likely to focus on showing his flock the path leading to spiritual redemption, while urging them to reject political and societal corruption, and to take a stand against the oppression of the poor.

Now he has turned the heat up a notch with his latest book, In Turbulent Waters. It was unveiled last November at a grand book launch held at the St. Mary’s College auditorium, which was very well attended. St. Lucian poet and overall winner of the 2015 OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature, Vladimir Lucien delivered the feature address. A work of fiction, it revolves around the life and priestly vocation of Fr. James Laport, a young Catholic cleric from the fictional Helen Island, and the blistering rite of passage that he’s forced to endure as he pursues his calling.

Like most youths growing up in Helen Island during the first half of the 20th century through to the early 70s – a time when ‘television was just a name’ and storytelling or listwa was a popular mode of entertainment – James Laport was born to a working-class family on the outskirts of the capital, Félicitéville. As children, he and his siblings were often regaled with frightening tales of black magic, witches and sorcerers, and stories about Tim Tim, KonpèLapen, KonpèTig, BèfLouwa, lajables and jangajé, and men transforming into creatures equipped with extended genitals and entering people’s homes through keyholes to sexually molest women – all of it gleefully recounted to them by their parents and the elders of the community.

Unlike his father who was a ‘seasonal Catholic’ and occasional churchgoer most of his adult life, James Laport’s mother was a PotoLégliz and presumably had some influence in his aspirations to join the priesthood. Throughout his teenage years and early adulthood, up until his assignment to the Archangel Parish Church in Geckoville to prepare for his ordination, James had always dismissed stories about black magic, ghosts and spirits as mere ‘phantoms of creative imaginations,’ notwithstanding they often gave him the creeps as a kid.

Fresh out of university and refined by his interaction with highly cultured and Westernised intellectuals who behaved as if their new-found enlightenment was superior to that of the people who held on to the old myths and legends,’ Fr. Laport soon discovers, to his dismay, that those legends are still very much alive in the hearts of the faithful, many of whom view them as metaphors for the ‘high occult sciences of the day.’

Soon after taking up his duties as an associate pastor, James Laport has his first rude awakening when a woman approaches him with her infant in her arms and begs him to help the child who is seeing spirits. She’s the first of a string of parishioners who turn up at his doorstep, pleading with him to deliver them from all manner of demon possession, ghostly hauntings, obeah spells, ritual murders, occult attacks, Black Masses and human sacrifices.

In one of the more poignant episodes, Fr. Laport catches sight of something unusual in the midst of a gathering at a ‘Praise and Worship’ celebration at the town’s playing field – a pig standing on its hind legs. A terrified altar server blurts out that it’s a pig with a human body. Fr. Laport quickly sprinkles the gathering with holy water and the being immediately makes a panicked dash to try and avoid the water. Several bystanders point to a woman in the crowd and begin shouting in panic, “Miankochonmounanpaminouwi.” (There’s a human pig among us). The woman suddenly grunts and a few people in the crowd recognise her. They plead with Fr. Laport to take her into the church and pray over her.

As the story progresses, more parishioners seek Fr. Laport’s help in exorcising demonic spirits and freeing people from occult spells. With each incident, the ordeal grows more terrifying and bizarre. Fr. Laport becomes so overwhelmed, a visiting priest is forced to come to his aid and teaches him and his fellow cleric, Fr. Fallon the principles of exorcism.

It has now become impossible for the beleaguered cleric to ignore the reality that within the very walls of the churches there are individuals who have made a conscious decision to explore the occult with the sole aim of securing personal gain or to inflict pain and suffering on those whom they despise or regard as their enemies. They are two-faced characters who live duplicitous lives and comfortably straddle two worlds – the sacred and the profane. The gravity of the situation and the catastrophic repercussions for the society are driven home to him when a local politician confesses to him, ‘Father, when it comes to elections, if one has to sleep with the devil to win, that’s what it takes.‘

As pleas for deliverance continue pouring in from his parishioners, the full implications of religious assimilation and syncretism become apparent and Fr. Laport realises how susceptible the island’s communities have become to those with dark and malicious intentions. This takes a heavy toll on the overwhelmed cleric. Like the Biblical prophet, Jonah he begins to despair and over and over again he feels the urge to escape from it all and ‘flee from the presence of the Lord.’ But each time his faith in Christ lifts him up and stiffens his resolve, and he proceeds to confront the hidden and traumatic realities of daily life in Helen Island, not just to help the members of his flock cope with the horror of it all but also for the sake of preserving his own sanity.

Although In Turbulent Waters is presented as a work of fiction, Fr. St. Rose makes it clear in his introduction that the use of fictional names and places is solely to protect the identities of individuals.

The obvious inference from that is clear; while the characters and setting may be fictional, their life experiences are anything but, including that of James Laport. Those who know Lambert St. Rose well would find it hard not to see in James La Port a reflection of Fr. St Rose’s own life experiences while serving in St. Lucia and other parts of the Caribbean.

He says his aim in writing the book is to show the reality and gravity of ‘cultic activities’ and the debilitating impact they are having on people’s lives and on the communities. ‘Baphomet wields a heavy hand in many national decisions, supported and encouraged by those considered as highly civilized persons,’ he adds.

The writing style he employs does not strive to conform to the conventional literary form and structure. Instead, he creates a series of vignettes and uses a format and cadence that are more akin to St. Lucia’s ‘Listwa’ tradition, sometimes reminiscent of the oral storytelling device of ‘Kwik-Kwak.’ It is also spiced up with copious flashes of wit and humour.

In Turbulent Waters doesn’t come across as the cerebral indulgence of some armchair intellectual. It is a gripping tale told with raw and disarming candour and in a matter-of-fact way that draws you in and keeps you hooked from beginning to end.

Fr. St. Rose no longer manages a parish like he used to due to ill health. But judging by his new book, he’s not about to let sleeping dogs lie nor does it look like he intends to ease up on those he berates as ‘vagabonds of culture and squanderers of tradition,’ men and women who, according to him, have “radically departed from the objectives of Listwa Time: the perpetuation of holistic genuine human growth and development, and the avoidance of evil at all cost.”

In Turbulent Waters is available at the following places in St. Lucia: The Chancery Offices, Vigie, The Folk Research Centre; St. Augustine Bookshop, and Bezata Gifts & Graces Bookshop in Castries.

Copies are also available online at Amazon.com, Barnes & Nobel and other major online bookstores.

![Simón Bolívar - Liberator of the Americas [Photo credit: Venezuelan Embassy]](https://thevoiceslu.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Simon-Bolivar-feat-2-380x250.jpg)