THE views I share here are solely mine and do not reflect the views of any entity with which I am associated. Moreover, I am not a lawyer, and so, I cannot claim my views have any legal probity. Here, I rely on my background in personnel management and industrial relations, to try to make sense of things.

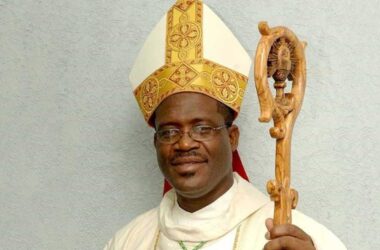

This commentary was about 75% complete, when Dr. Hyginus Leon, the 6th President of the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB), resigned his post with immediate effect. Dr. Leon was elected to the post at a special meeting of the Board of Governors (BOG) held on January 19, 2021. He began work on May 4, 2021. In a statement released on January 17, 2024, that shocked the region, and the international finance community, the CDB acknowledged that Dr. Leon was the subject of an “ongoing administrative process” and had been sent on administrative leave, until April 16, 2024. The reason(s) for such unprecedented action is/are unknown, which has provided ideal conditions for rife speculation.

The Context

The CDB is an international financial institution of solid repute. It has a body of administrative laws and processes-some of which were instituted by its founding President, Sir Arthur Lewis-that have stood the test of time. Moreover, it has the money to get the best legal advice. From this, one is tempted to conclude that: (1) senior bank officials who initiated the administrative process, involving their President, have assured themselves they are batting on a “flat wicket” with no legal or procedural demons in it; (2) the impacts of their decision, including harm to the Dr. Leon’s reputation and that of the Bank were carefully assessed; and (3) they considered and dismissed the option of allowing Dr. Leon to continue in his post, during the administrative process.

Natural Justice

We should also note that the President was not “summarily dismissed.” I assumed this was in deference to the “principles of natural justice,” which require that an accused person must be given an opportunity to answer any charges against him/her before an impartial Tribunal. Consistent with this principle, I and countless other Caribbean citizens, presume Dr. Leon to be innocent, until his guilt is conclusively proven. Further, I assumed Dr. Leon had not resigned earlier, either because he did not know the details of the charges against him, or that he was informed, but believes he is innocent.

According to his letter of resignation issued through his lawyers, Dr. Leon claims to have been informed about the “general, barebones nature of the wide complaints levelled against him” and that these complaints “…continue to be bare, nonspecific, allegations without condescending to any particulars of the circumstances of the complaints, including, but not limited to dates, subjects, places or references to the evidence to support the grave and serious allegations made against (him) our client.” Further, the letter alleges that 40 hours AFTER his leave expired, Dr. Leon received a letter, signed by the chairperson of the Office of Accountability (OAC), on behalf of the Board of Directors (BOD) of the Bank, notifying him that his administrative leave was being extended.

One of the elements of the principles of natural justice is that no one should be a judge for their own cause. Consequently, in his role of chairman of the BOD, Dr. Leon would not have been party to the decision to initiate an administrative process against himself.

Given the circumstances, the harm Dr. Leon would have suffered, following the mere announcement of the administrative process would have been substantial, approximating the harm he would have suffered, if he was dismissed. This leads me to wonder, whether-in keeping with the rules of natural justice-Dr. Leon ought to have been allowed to defend himself BEFORE the administrative process was initiated. At the same time, it is reasonable to argue that any preliminary harm suffered by the CDB could only be relieved if it emerges that its actions were justified. However, what is clear is that the Bank did not have the hard facts to justify recommending to the BOG that Dr. Leon be summarily dismissed.

Digging Into The Weeds

To better appreciate the state of the wicket Bank officials are batting on, I reviewed the decision-making landscape of the CDB, including its Charter (Agreement), Bye Laws, Code of Ethics, and other relevant, legal, and administrative instruments. While Dr. Leon’s resignation renders this exercise moot, I share my findings, for what they are worth.

The Agreement

Article 25 of the January 1970 Agreement (as amended) establishing the CDB, provides for a BOG and BOD, a President, one or more Vice-Presidents, officers, and staff. All powers of the Bank are vested in the BOG, including the power to elect the President and directors of the Bank. While the BOG delegates some of its powers to the BOD, it retains full power and authority over ANY such matter. Instructively, the BOD cannot dismiss the President. According to Article 33, the President is elected, or dismissed, by a vote of not less than two-thirds of the total number of governors, representing not less than three-fourths (75%) of the total voting members. I will return to this.

Article 28 (3) of the Agreement allows the BOG to establish a procedure through which the BOD may obtain a vote from it on a specific question, outside of a BOG meeting. Based on the professed ignorance of Caribbean leaders-who are members of the BOG-about the circumstances leading up to and including the administrative process, we can conclude that the initiation of such a process in respect of a President, is not one of the “questions” covered by this procedure. We might question why this is so, given the weightiness of that matter.

The President is the CEO of the Bank and chairperson of the BOD. He acts under the direction of the BOD, meaning that he cannot take unilateral decisions. Article 30 of the Agreement gives the BOD responsibility for directing the general operations of the Bank. The Agreement does not expressly give the BOD the power to take disciplinary action against the President. Some regional commentators have argued that only the BOG should have that power. If this power was delegated by the BOG to the BOD, then Caribbean leaders appear to not be aware of this.

However, Articles 49 and 57 of the Agreement gave me reasons for pause. The bearing of these Articles in the context of the administrative process instituted against the President is significant. Article 49 gives the Bank total immunity from “every form of legal process, except for a range of financial matters.” I take this to mean that the CDB cannot be sued by its staff. Article 57 of the Agreement empowers the President to waive any immunity exemption, or privilege of any bank employee “where such immunity would impede the course of justice and can be done without prejudicing the interests of the Bank.” Intriguingly, the BOD can waive the immunity of the President and Vice Presidents. There is no indication in the Agreement that the BOD needs the permission of the BOG to do so. However, I do not believe it would a healthy thing for the BOG to be involved in disciplinary processes against its staff, even a President.

Code of Conduct (COC)

This Code sets out the core values, standards, and specific rules of conduct that staff members must observe in discharging their duties. It prohibits all forms of harassment, intimidation, fraud, corruption, interference, violence, “working under the influence” and conflicts of interest. Violations of the Code could lead to sanctions. However, the Code outlines procedures for “…fair, ethical, and transparent handling of breaches of the Code.” Only the President can dismiss a member of staff for any breaches. Upon appointment, each staff member is supposed to sign a certificate of acknowledgment (COA) of the Code. It is not clear whether the President is a “staff member” of the Bank, as this term is not defined in the Agreement. However, if Dr. Leon signed the COA, then it binds him.

In their letter announcing Dr. Leon’s resignation, his lawyers identified the Bank’s Oversight and Assurance Committee (OAC), as the source of the letter to Dr. Leon extending his administrative leave. According to the CDB’s website, the OAC is an arm of the Office of Integrity, Compliance and Accountability (ICA) which is mandated to operationalise, manage, and refine the CDB’s Strategic Framework for Integrity, Compliance and Accountability. This Framework “articulates a comprehensive strategy for institutional integrity (fraud and corruption), ethics, whistleblowing, anti-money laundering, countering the financing of terrorism, monitoring financial sanctions, and accountability for environmental and social harm caused or likely to be caused by projects financed by the Bank.” While operationally, the ICA is an independent office, administratively, it reports to the President and functionally, to the Board of Directors through its OAC. This confirms the authority of the OAC to investigate allegations of misconduct and to report its findings to the BOD. What I have not been able to establish, is what action the BOD can take, upon receiving information from the OAC, and whether it can unilaterally direct a President to take administrative leave.

The World Bank (WB) Standard

The decision-making architecture of the World Bank (WB) mirrors that of the CDB, but only as far as it provides for the existence of a BOG, a President, and Vice-Presidents. The Executive Directors (EDs) of the WB perform similar functions as the BOD of the CDB, under delegated authority from the BOG. However, whereas the CDB’s President is elected and dismissed by its BOG, in the case of the WB, the President is selected by EDs and ceases to hold office when EDs so decide. The role of the World Bank’s BOG is restricted to setting the salary and contractual terms of the President.

The Disciplinary Procedures set out in the WB’s Staff Manual gives a staff member the right to respond, orally or in writing, in no less than 5 days, to allegations of misconduct during the investigation. Moreover, the rules require that a staff member must be provided with a copy of the final investigative report, so he/she can comment on the findings.

Conclusion

The saga that has unfolded at the CDB over these past 3 months, and which reached its peak with the resignation of its beleaguered President, must rank as one of the most challenging periods in the Bank’s history. I refrain from describing it as a “dark period” as others have done and will wait to see how things go from here. However, to my “avoka ti papyé” mind, there are certain grey areas in the CDB’s set-up and in its disciplinary procedures that need to be urgently fixed. The adoption of the World Bank standard might be the way to go.