THE yearnings for power and wealth of the stone-cold dead British Empire echoed amongst the older generation throughout the shires of Britain during the Brexit campaign. Those yearnings reflected themselves in the support of the older voters to leave the European Union (EU) as an assertion of their sovereignty and the exceptionalism of Britain.

Britain was indeed once the ruler of the world, a place it achieved by slavery, exploitation, military coercion and by ruthless application of the dictum of Julius Cesar, divide et impera (divide and conquer). Fortunately for Britain, this ancient and archaic belief in fundamental British superiority has not poisoned the minds of a more open and realistic younger generation.

Despite the fact that the British history they learn in the official school curricula is sanitized of the evils perpetrated in the name of Britain’s glory and its accumulation of wealth, the educated younger people have a greater sense of the diminished circumstances of Britain and the need for its deeper integration in Europe. That, too, was evident in the demographics of the Brexit vote.

The mythology of the benefits of British colonialism, its fostering of democracy and its development of the countries and peoples over whom it ruled, has been exploded in a gripping new book entitled, “Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India”, by Indian parliamentarian and former government minister, Shashi Tharoor.

The accounts in the book of “the long and shameless rapacity in India” have compelling parallels with slavery and indentured servitude in the West Indies. The cruelties and barbaric acts, including the slaughter of women and children at Amritsar under the command of Brigadier General Reginald Dyer, are akin to the killing of slaves throughout the West Indies who rose up in defiance of their captivity and their dehumanisation, except that the people at Amritsar had no weapons of any kind and had gathered not in protest but to celebrate the major spring festival of Baisakhi. As Tharoor records, “Dyer ordered his men to keep firing till all their ammunition was exhausted”.

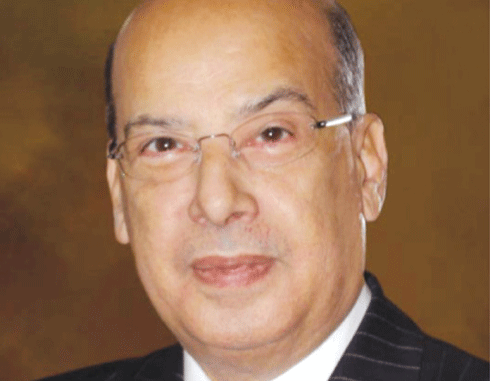

Tharoor is no wild-eyed anarchist. He is a seasoned diplomat who served for many years in various UN agencies rising to the level of Under-Secretary General during Kofi Annan’s stewardship. He was also a candidate for the Secretary-Generalship in 2006 losing to Ban Ki-Moon. His narrative is underlined by a sense of outrage, but at no point does it descend to unsubstantiated allegation and accusation. It is a careful, meticulously researched study expressed in eloquent use of the English language – perhaps the one useful legacy left by Britain to the countries of its former Empire. At least it facilitates international discourse among the majority of the world’s people.

However, as Tharoor points out, in the case of India, educating Indians was not done for the sake of Indians; it was done to satisfy British needs in India. The same can be said of the West Indies where such education as was established was geared to filling positions in the colonial civil service. The structure, which was left in place at the independence of the West Indian countries, was ill-prepared for the demands of global competition.

The British acted in the countries it controlled in Britain’s interest with no regard for the long-term consequences of their actions. Thus, Tharoor relates, the destruction of Indian forests and wildlife occurred at a galloping pace for three main reasons: “to convert the land into commercial plantations, especially to grow tea; to make railway sleepers, and to export timber to England for the construction of English houses and furniture”.

The consequence was deprivation of native tribes of their land, elimination of animals and the ecological devastation of vast areas. Similarly, in the West Indies, on the island of Antigua, originally thickly-wooded forests were cut down to facilitate sugar production. The result in Antigua is the absence of sufficient trees to attract rainfall, long periods of drought, and a heavy reliance for water on modern and expensive technology such as desalinisation and reverse osmosis plants.

In making his compelling point about how Britain became rich at the cost of India’s impoverishment, Tharoor recalls that the East India Company was established in 1600 as the instrument through which Britain plundered India. At the Company’s establishment, Britain accounted for 1.8 per cent of global gross domestic product and India 23 per cent.

India was one of the richest and most industrialised economies but it “was transformed by the process of imperial rule into one of the poorest, most backward, illiterate and diseased societies on earth by the time of our independence in 1947”. By then, India’s share of world GDP was just 3 per cent while Britain’s was three times as high.

Similarly, sugar production from the West Indies enriched Britain on the backs of slavery and indentured labour. Britain’s parliament was filled with West Indian sugar plantation owners who bought their seats with the proceeds of exploitation, dehumanisation and brutal slavery. Today, the legacy is held in Britain by banks such as the Royal Bank of Scotland and Barclays and in the wealth and positions of the elite and even cultural institutions such as the Tate Gallery.

Tharoor also takes apart the British claim of uniting India from warring principalities and statelets. It is the British, he asserts, who through their deliberate policy of divide and rule, promoted and entrenched distinctions between Hindus and Muslims, as well as between Hindu castes, and set the stage for the partition of India into India and Pakistan with the legacy of hostility that characterises their relationship today.

The British did the same in the West Indies, most notably in Guyana, but also in Trinidad and Tobago, where they created conditions for hostility between descendants of African slaves and Indian indentured labourers that continue to plague those countries. Without the instrument of divide and rule, how else could a handful of British civil servants, police and soldiers control the significantly larger numbers of people they exploited?

Few sensible persons would hold today’s generation of British people accountable for the atrocities of previous generations; certainly, not the young generation. But the history of Britain is stained by the excesses of their Empire. Tharoor is not an advocate of reparations as is demanded in the former West Indian territories; he favours a manifestation of atonement similar to the Kniefall von Warschau – when in 1970, Willy Brandt then Chancellor of Germany, “sank to his knees at the Warsaw Ghetto to apologise to Polish Jews for the Holocaust”. It will probably take another generation in Britain before such a thing occurs.

Tharoor’s book is about Britain in India, but its story is equally about British imperialism from whose exploitation West Indian peoples were also sufferers.

(Inglorious Empire: What the British did to India, by Shashi Tharoor, published by Hurst & Company, London)

Responses and previous commentaries: www.sirronaldsanders.com

(The author is Antigua and Barbuda’s Ambassador to the US and the OAS. He is also a Senior Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies and the University of London and Massey College in the University of Toronto. The views expressed are his own)